Blood BrothersA Story by MalenkovTwo close friends, whose fate and destiny diverge in their encounter with the system.

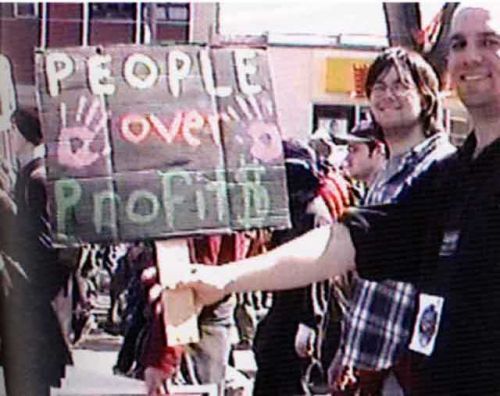

Blood Brothers by Malenkov I scalded my tongue with my cappuccino with the shock of seeing him. Wedged in a seat, two rows in front, among the grey suited commuters, on the Central Line train squealing home through the London Underground to Bethnal Green. I feigned engrossment in the Financial Times, evading the sardonic smile, the severe white robes flowing about the hairy ankles, the pointing bushy beard cascading about the midriff. When next I dared a glance, the square of his cap bobbed among the commuters’ heads ejecting through the train doors. I breathed once more. I was dressed in a black, city issue pin-stripe. Returning home--enervated from ten-straight-hours of fickle corporate politics. When I got home I pumped every friend and half acquaintance in the area for news. So, he was back. Probably nursing his hate like a potted plant. Thirty one years old and, rumour had it, living with some bride he’d picked up in Karachi. Doing what? Indoctrinating for the next offensive against the Establishment? Rumours, it was true. But where there’s smoke there’s fire. My eyes tracked the NASDAQ market ticker streaming along the bottom of the CNN TV Newscast. Money, markets, brutal reality--they were the sensible clay of my life. Trisha, busy stoking the wok in the kitchen--stir fried ginger, Atlantic tuna and mange tout hanging pungent in the air--shot me a questioning glance as I quenched the dregs of gossip from the phone. I was sipping a glass of blood red Pinot Noir and flicking the cinders of a Marlboro in an ashtray. An old school friend had just abandoned the juicier story of Shelly. And as I paced about the living room sofa, phone set to loud speaker, was inflicting a drawling monologue--on his lack of sex life, imminent sacking, the drivel of his life. When the wheezy, cigarette scoured voice, paused for my opinion, I slipped in that I had a migraine, recommending we catch up over a pint in the Fox and Hound, and hung up. The look I gave Trisha was fretful. “What was that about?” Trisha had come out of the kitchen. “Bad news, I’m afraid,” I said. My stomach knotted, my jaw clenched. He could show up anywhere; on the underground, at the supermarket, he might even come to the office. But what could I do? Lock myself in the house and mope? “Is it really that bad?” Trisha said. I pushed away the plate of nibbled tuna steak and buried my head in my hands. * * * Twelve years ago we’d been friends. Blood brothers. Each day, we’d walked the same five miles to school together, been neighbours on the same Newham council house estate. As sixteen year olds, we waged war against corpocracy in senseless acts of destruction. Using house keys, we’d scrape the lacquer of gleaming BMWs, bend double the silver lady atop Rolls-Royces. During the Test Match season, we scaled the park gates at night, prowled among the rows of pavilion tables popping crates of Dom Pérignon bottles till champagne bubbled over the red carpets. Each Saturday afternoon we’d hide under the shady eaves among the bunkers of Wanstead Golf Course--waiting to snatch golf balls as they plopped in the sand. Then we’d taunt the pale faced, tweedy executives until they waved their six irons in fury and chased us till they puffed red in the face. Even back then, Shelly dreamed of an activist movement: fighting corporate abuse, campaigning for people’s rights. He was given to speechifying. On a freezing Sunday afternoon, he’d drag me to the Speakers Corner in Hyde Park, climb aboard a soap box and harangue the bystanders and picture snapping tourists; His militant babbling declaiming unscrupulous advertisers corrupting our freedom, and the corporate rape of democracy. On night raids we’d deflate the Michelin man, splatter the Esso tiger with paint, and smear beards on the poster models. Corporate resistance, he’d say. Privately, I saw our tantrums as venting existential rage. At one point, we assaulted the flyover construction tearing a swathe through the heart of the acres of forest behind our tenements--we were around fifteen. It was then I had my first hint of just how extreme Shelly could be. I’d never considered him unhinged--eccentric, maybe. For sure, there was the vehement blather whenever we sauntered along the shopping mall stores--Corporates! he’d spit, eying the drones of strolling shoppers, Making slaves of us, turning us into mules--what for? A few lousy dollars more. But none of this, I deceived myself, was any different from the peevishness of youth. He’ll adjust, I told myself. Now, sabotaging the flyover, I saw Shelly’s behaviour transgressed harmless rebellion, verged on lunacy. Admittedly, there was a cathartic quality to all that destructiveness. But his anarchism repelled me. I grew distant. We’d planned our invasion of the construction site with the precision of Dam Busters. Donning night black costumes, we infiltrated the site like fleet footed jaguars, clipping holes in the chain wire fence with industrial cable cutters, and puncturing water pipes till they flooded the maintenance ditches. We clambered up a flyover column--spray painting “Hands-Off Our Forest!” in luminous letters. Fate intervened. Engrossed in defiling the wind shields of bull dozers with anti-corporate slogans, we didn’t hear or see the two soft booted patrol men ambling up on us, curving searching flash-light arcs through the pitch of midnight. We were handcuffed, frogmarched, bundled in a patrol car. Separated. Dumped among convicts in freezing cells. They interrogated me. I was no hardened criminal. No martyr to some quixotic crusade to tilt at windmills. I wanted a warm bed, a hot water bottle. I begged the sergeant not to tell my mother. I broke. Confessed. Rumour had it Shelly spent six months in a Borstal juvenile correction centre. Clearly, Shelly was unrepentant: He emerged outside the school gate. Handing out flyers with slogans like:10 Non-Violent Ways To Resist The Corporate Control of The U.K. During the summer vacation he visited Trisha and me in Kent, at her parent’s detached three bedroom Mock Tudor cottage. From the minute he arrived by train he paced around the living room--Raring round the plush rug with his crew cut, punctuating his monologues with swishing chops. From the head up he was twitchy; the corner of his mouth spasming so restlessly, my fingers tap danced involuntary. Neck down, he was wolfishly lean in baggy desert combat fatigues. Between his soliloquies I tried to deflect him back to sober topics. I argued about the Real Politik necessary to balance the rich, against the poor. But like the stuck needle of a record player his mind cycled along its single grove. I humoured him. My sunken head mechanically nodding at intervals, I smiled at appropriate phrases. Circling the tip of my thumb around the wine glass rim of a dry Cabernet Sauvignon--indulging the wine’s bouquet of violets, blackcurrant, cedar and spice--I prayed patience would blunt his sermons. Come midnight, Trisha gone long to bed, he leaned forward in the arm chair opposite--Elbows edged out, half his profile cut by the sharp light of a table lamp by which I now sat. From what I gathered from his ramblings, he’d left a well paying investment bank internship for some activist campaign. He finished that comment, plunging into a pregnant pause, and reclining into the recess of the arm chair--silently scrying the surprise I stifled from running across my face. He was making a name for himself. Prostituting the London University tour-circuit: Agitating militancy among unformed minds with fiery polemics. Propagating practical activism, as he described it. Forming splinter cells here. Sparking wild cat protests there. Beguiling innocent students into flinging their bodies against police barricades and batons. He elaborated his vision of running an Indie TV company to--in his words--broadcast 198 Ways to Wage a War of Non-Violent Corporate Resistance. He wanted to stir people to rise up. Lift the veil of corporate lies. I provoked him: implying in couched sentences that he’d traded stability and opportunity for the fool’s gold of lost causes. His mind fought me--a vault slammed against reason. He clung to us for a teeth-grinding week. Shortly after that charming visit, he began sending packages of books: Klein’s No Logo; Chomsky’s Thought Control in Democratic Societies, Nader’s Taking on the Corporate Government. Deleted the moment they swarmed into my inbox, emails like the following came: ONE COMPANY HAS FILES ON 185 MILLION AMERICANS. THE CORPORATE LOBBY IN WASHINGTON STIFLES LEGISLATIVE ACTIVITY. THE REALITY OF BIG BUSINESS TODAY IS OUR BIG DIRTY SECRET. THERE CAN BE NO DAILY DEMOCRACY WITHOUT DAILY CITIZENSHIP. WE MUST OPPOSE ECONOMIC FASCISM EVERYWHERE. For a while I tried to fathom the intent behind his madness. Was he trying to convert me? Intimidate me? Was he so cracked as to really believe we actually shared something in common? I brushed it aside. I had exams to focus on, a life to lead. Eventually they stopped. Rumours trickled to me. Among the demonstrators’ faces flashing on TV, now and then I’d glimpse his craggy nose--among the arm linked students, marching into the mounted police and water cannon. More news from the grape vine dribbled in. Then Interpol arrested him--I breathed a sigh of a relief--in connection with demonstrations among British campuses. Trisha and I got engaged. I got my first job at Rothman & Sons Corporate Financiers; accepted with stoicism the grinding tempo of the rat race. Then I got the call. Just as I’d gotten the after-ten cab home, my psyche blunted into apathy by ten straight hours of goggling monitors full of cash flow forecasts. I’d just flicked open the green sleeves of a folder--Schweb’s Finance Analyst Study Guide. In no mood for chit chat. “Listen, Harry, it’s me, no, please--Wait, don’t hang up. We go back, remember? This is dead important,” he said. I hadn’t spoken to him in ages--in God only knows how many years. We’d drifted poles apart. Yet he breathed down the receiver in the same mesmeric voice, as if we’d just shared a Budweiser in a West-End bistro. “This is not the time,” I said, firmly. I checked my Rolex; It was 3:00 AM. I pictured my remaining three and a half hours of sleep slipping away like sand--all I had to face the morning rush-hour crush. I pushed the study guide away. “The b******s, the sons-of-b*****s, no, no, I don’t have time to explain. I need you to do one thing for me. Just a little thing. . . .No, no, no, just relax--Will ya? . . . No, there’s no danger. Just stick up for me--if anybody comes around asking.” The phone went silent. I looked at my cold tea, thought of the bed warmed by Trisha upstairs. The voice came back. “Will you do that--for me? For old times sake?” “Fine,” I said. Time passed: In blind routine, crammed exams, a busy social life, and the grind of a six month job probation at Rothmans. One and a half months later, munching a lunchtime tuna mayo sandwich, this scruffy fellow comes bounding up to my cubicle. At first I took his crushed gait and scuffed leather shoes for the company postman. I blanked him of course, annoyed by the raspy breathing hovering by my cubicle opening. I made him wait, while I punched the last of the projections into the spreadsheet--only then did I swivel in my chair to face him. “Can I help you?” I asked. The boss’s assistant was chattering from the next cubicle row about the specifics of some client acquisition. Did I know a Shellwood C. Courtney, the man asked. I didn’t answer at first, looked the stranger up and down. “What of it?” I said. He flipped out a wallet, tapped the badge with a long, pointy, dirt encrusted nail. “Scotland Yard--Intelligence. I have a few words I’d like to ask you, if you wouldn’t mind.” The chatting stopped like someone pulled the plug on a tape recording of white noise. “Come this way,” I said, walking ahead to find a quiet conference room--away from prying eyes. He certainly didn’t look an intelligence officer. I’d pictured more a Bond type: suave, easy savoir fair--at least designer jeans and a Tag Heuer watch. But he was scruffy as an alley cat. Dirty stubble smeared around a double chin. He certainly wore the plain clothes, of a plain clothes officer: shabby jeans--hardly fit to grace the tailor made elegance at my company. Were it not for the badge, I’d have called for security. He skipped the small talk: launching into a flood of questions the moment we sat down. How had I come to know Shellwood, he asked, in that grating uncultured accent. Did I have any idea where he was about these days? Had we contacted one another recently? Was the man dangerous? “Dangerous?” I repeated. “In what respects?” “Well,” the man said, putting his muddy boots on the conference desk--scratching the delicate mahogany veneer. He waited. Lit up a cigarette. I resisted warning him of the company no-smoking policy. Then he leaned forward, pointing his cheap cigarette in my face. “Is he subversive?” he wheezed. I reflected a minute, thought about our past, the visit to Kent, the packages and emails, Shelly’s hunted voice on the telephone. I came close to actually asking the agent what business it was of his, in any case? Was Shelly wanted in connection for something illegal? Could I in some way be implicated? For an instant, I scanned his face for signs--pictured the damaging rumours of past transgressions re-emerging into the twilight of water cooler gossip. What ought one to say? Then I leaned back. Dropped my eye to the floor and mumbled that in my opinion the man was the most dangerous menace to society I’d ever met. A year rushed by erasing Shelly and the agent like a bad dream. Now he was back. Slicing the present like a reopened wound. * * * “What are you afraid of?” Trisha asked. “That he’ll organize a mass protest rally outside our door or something?” It was dark. Crickets chirped, and lawn sprinklers softly spat, wafting in on the tail of a cool summer breeze from the open window. I poured myself another glass of Pinot Noir. “Don’t be silly dear,” I said, “that’s not it, but think of the neighbours, or--my God--if they ever found out at work.” She laughed. “Neighbours? I thought you said you were best of friends.” I nodded, that was precisely my predicament. I sipped at the tea. “Look, it’s not like you’ve got to invite him in for a game of bridge while he lectures us on third world politics--or whatever it is he’s into these days. . . .And it’s hardly likely he’s going to come knocking on our door any time soon--unless you expect him to come abseiling down the chimney or something.” She was in the kitchen, putting the crockery in the dish washer. “Are you afraid he’ll do something?” “I don’t know, I don’t know,” I said. “I mean, we’re not teenies with a mission to prove anymore or anything like that.” I considered my house, listening to the hiss of the kettle boiling. The house was cozy. Elegant and English. Gleaming his and her four-wheel drives in the driveways, a solid-oak panelled porch and stained French arched windows. Stylish. It stood out as the sort of house that marked me a “corporate w***e”--as Shelly used to call it. I looked up from my wine. “He might,” I admitted. Trisha turned from the dishwasher to look at me, eyebrows raised, wiping her hands on a towel. I read her concern. “There’s no need to panic--” It wasn’t that I was afraid. Worse, I imagined him silently condemning me: I’d become the kind of lackey of capitalism he detested. That’s why I didn’t want to see him on the rush hour tube, or walking by our perfect striped lawn, his shoulders twitching with subversive rage. “Darling,”--she was stroking my hair, kissing me softly in the nape of my neck--“just relax, will you, you’ve got enough on your plate without adding to it.” She was right. I was putting together a presentation for a take-over of the East Docklands Steel Works--for our client, a Tatzuki-Schmidt Consortium. Charlie Rothman had asked me to scan the fine print for some way to sweeten the restructuring to the union and a solid hour loomed ahead of me, at least, if I was to finish the projections for our morning meeting. . . .The thought of those lost jobs brought me back to what Charlie had said a while back, after I first joined, “Harry, if you want to get ahead in this game you can’t afford to have a conscience. You need to think like a banker and not some bloody fool of an idealist.” Charlie was right. But still, it was condemning another community to the dustbin of economic history. It’d be a blow, certainly--cost the jobs of half the steel workers in the area--but those were market forces. “Don’t worry about it dear,” she was murmuring, running a finger along my lips, lulling reason itself, making me drowsy. “After all, the chances of meeting him again must be a million to one.” * * * The day was alive. The sky pulled tight across the sky scraper crowded dome of London. The watery disc of the sun playing peek-a-boo through the crowns of coniferous spruces and ragged sycamores. We’d come back from shopping, exhausted, after gutting Harrods in a fit of marital therapy--and put enough on the credit cards to swallow the GNP of three small African nations. Now, I sat beside Trisha on a park bench in Hyde Park, just across from Speakers Corner. On impulse, Trish had suggested a park bench picnic in Hyde Park on the way back in the train. May was nudging away the rain clouds; there’d be the scent of fresh-cut grass filling the air with the aroma of Spring; the casual murmur of lovers nestling cheek-to-check on benches. Why not? I’d concurred. I’d given the presentation the previous evening. In the darkened elegance of Rothman’s executive suite I’d laid out the specifics of the restructuring: Spilling out the fine details in an orgy of techni-coloured bullet points more esoteric than Amenhotep’s hieroglyphics. As I finished the peroration of my speech, I squinted up through the projector glare, into the rows of mummified suits before me--watching understanding peeling lips open like ancient papyrus. Now, bending to hear Trish chatter about the bargains she’d acquired at Harrods, my mind wandered to the glimpse I’d won of Charlie Rothman’s thin wisp of a smile--I pictured my career one rung higher on the greasy corporate ladder. I sat there on the bench, lost in thought when, from the corner of my eye, a shadow parked at the end of the bench. At first, I dismissed the man as one of Hyde Park’s detritus--scrounging pennies to feed an insatiable crack or whisky habit. Why the deuce couldn’t the man find some other person to pester? I whipped around, ready to give him a piece of my mind. It was Shelly. He stood there, head erect, under the drooping branches of a weeping willow at the far end of the park bench. He was wearing a long chequered shirt, like a vaguely afghan shawl that swept in long billowy pleats around his sandals. The skin was anaemic, hard baked clay, the cheeks two bloodless sacks. When he looked up, his eyes were watery. “Harry,” was all he said. I was at a loss. I felt I was playing a bit part in some surreal comedy; acting out a ghastly nightmare from which I couldn’t wrench myself. My initial impulse was to stagger away, feign non-recognition, but now, with Shelly sitting before me, I could only open my hand and politely invite him to sit at the vacant space next to me. “Oh no,” he stammered, “I was just,” he pointed along the path by way of explanation, “walking--happened to notice you, sitting here, felt I’d just say. . . hello. That’s all.” “Don’t be silly,” I said, yanking aside piles of shopping bags scattered on the bench as if my life depended on it. “Here,” I was practically begging the man, “please, take a seat”. I began extracting cashmere cardigans, embroidered herringbone shirts--out of the big green and beige Harrods bags--heaping them about the bench on the gravel path. “Would you care for chocolate truffles--” I said, fishing in the bags, “We picked up some absolutely marvellous delicacies from Harrods.” We were sitting so close, our knees almost touched. He took in the Speakers Corner with a glance over his shoulder and for a moment I half expected him to jump up and heckle the tourists. But he didn’t. He sat pole straight on the edge of the bench. “No thank you.” “Are you sure?” I said, “How about a bio-Atlantic salmon and ice-cucumber sandwich?” I was lifting packs of food out and holding them out; Desperate to offer him some sort of olive branch. “Water--,” he said, straining the words through the vice of his teeth, “if it’s not too much trouble.” I fell over myself assuring him how little effort it was on my part, took out a diet-coke and handed him a bottle of Evian and arranged a box of handmade French chocolate in the space between us. I was looking at the scenery like a tourist, he was determinedly studying his bottle of water--while Trish, arms bolted across her chest like straps of Kevlar, sealed the glossy line of her lips into the grimace she reserved for Hare Krishnas and was shooing away the pigeons sprouting around our feet. “So,” I said, all casual charm as if we’d just meet up for Sunday lunch, “how are things with you and your, ah, new wife then?” He sat there, staring into the distance at Speakers Corner. There was something bitter--chaste even--about the man; perhaps it was the beard, which lent him the air of a mullah. “Lot’s changed for Trish and I,” I said, more to make conversation, “it’s been hectic, I tell you, since we moved to Hampstead.” Trish whistled about her, the pigeons had taken on supreme importance. Lacking any response I considered joking about the old crusades--reconnecting to the common ground of our past--but thought better of it. “So,” I said, affecting what I hoped was an amicable manner, “it’s been quite a while, since we were . . . in contact. I expect you’ve had all sorts of interesting, adventures, then, eh?” I was fingering the collar which had started to gouge my neck. He seemed to take a somewhat exaggerated pause and fixed me with his bloodshot eyes. “I was in a correction centre,” he said, the vowels stabbing the air. I was up on my feet, offering Trish the candied orange--seized by the need to move and avoid. “You’d never believe that good old Britain has its own version of the gulags,” he said, the smile, faintly bitter. “Only it’s called a correctional centre here. At least the Soviets call it by a more honest name,” he said, his chin wire-taut. He took another look at the speaker, who was haranguing the passersby, and downed water from the bottle in noisy gulps. He leaned forward, an ugly grimace contorting his lips. “Still both lead to the same results. . . . Brainwashing, interrogations, solitary confinement--all the fine arts of psychological torture. Only when I begged did they promise to let me out--so long as I promised to stay a good boy.” He turned to face me, the smile on full-beam. “Thanks to you, I’m all corrected now.” He was pumping my arm. “Indeed I ought to thank you Harry,” his voice oozing sarcasm, “Why, were it not for you, dear honourable Harry, however would I have learned to see the error of my ways.” He let the pause linger long. I looked away, felt my cheeks burning. I had imagined a picnic, not some diatribe about water under the bridge. I hadn’t been the one lunatic enough to stir up insurrection. What the hell did he expect? The last thing I wanted to do was sit here listening to barbed comments while playing the pleasant English host. His flippancy demanded some kind of response--for honours sake. “Well,” I said, slowly--indignation pinching my voice into a whine, “if we play with fire, we’re going to get our fingers burnt. Aren’t we now?” He kept a pleasant calm upon this face. But he gripped his knees, screwing the plaids and pressing his elbows together rigidly. “They kept me in there a year and a half,” he said, his nostrils flaring. My feet were nervously shuffling. Something made me remember the phone call. The agent. Guilt. That was what he was after. Using the past like a bludgeon, bringing things up that should be decently buried. He watched as the speaker left the podium to a raucous chorus of heckling. “The man’s wasting his time,” he said, flicking up an index finger in the direction of the speaker. I raised my eyebrow at this cryptic comment, waiting for an explanation. “After all, you fight for others’ rights--rights they’re too cowardly to fight for.” He took a long sip of water, and held my eyes so long I had to look away. “But in the end, the people you fight for always betray you.” He stood, brushed himself off. “I think it’s time I took my leave. So long, Harry.” He gunned the same ironic smile on me then turned his back on us. Leaving Trish and I watching the receding figure crunching gravel underfoot, swallowed by the branches of the willow. --END-- ------------------------------------------------------- “Blood Brothers" appeared in the Summer 2009 issue of The Black Oak Media Magazine. Many thanks for your wonderful reviews and for voting for this. © 2020 MalenkovFeatured Review

Reviews

|

Stats

771 Views

5 Reviews Shelved in 2 Libraries

Added on February 12, 2008Last Updated on August 9, 2020 Tags: political, short story, fiction AuthorMalenkovFrankfurt, Germany, Hessen, GermanyAboutI'm a Brit, a child born to the war, the Angolan civil war my mother escaped from. So I grew up in the shadow of London--Small town of Ilford, Essex, right on the end of London’s Zone 6. Portugu.. more..Writing

|

Flag Writing

Flag Writing