Unpatriotic Teenage Shooting Victims Continue to Thwart the Constitutional Rights of Joe the PlumbA Story by Seth CasonA stronger revision of a piece I posted here last spring. This version, which differs from prior drafts in that I didn't fall asleep at the keyboard, is finally the final draft.

Unpatriotic Teenage Shooting

Victims by Seth Cason

And every year now like Christmas some boy gets the milk-fed suburban blues reaches for the available arsenal and saunters off to make the news,

--Ani

DiFranco

He’s

healthy, well-liked, and unassuming. The world doesn’t know his name, but each

day he draws closer to the opportunity, the exciting possibility of knowing the

world. How many people does one meet in a lifetime? How many ways do they

change and grow through one another? This morning, Valentine’s Day, he walks

into his high school carrying a brilliant bouquet of flowers for his

girlfriend. He’s athletic, smart, his adventurous and extraordinary destiny is

not one he’ll take for granted. And now, he’s discovered a passion for writing;

he’s got talent, he has the knack. His favorite class is creative writing, He’s

there now, in that classroom on the third floor on this Valentine’s Day, and

when the fire alarm goes off, like everyone else he leaves his seat and steps

into the crowded hall. His

signature photo has become an archived default, the front page of a legacy most

of us will never know. It’s where the impact is most visceral. His face is the

strike of lightning that blasts the same place twice, three times, four, five;

it’s the boxer’s upper-cut that connects with your jaw. You turn around, glance

back, another connection. But nothing in this world is immortal, no one is

exempt from the laws of physics, gravity, diminishing returns. For now he’s a

supernova, he’s coursing away at light speed, and he cannot halt and return

home any more than we can reach, jump, secure our grip around his ankle and

never let him go.

Joaquin Oliver is seventeen years-old. He’s a fusion of strength and

serenity, standing snug and bundled in the foreground of a winter beach, a

black knitted skullcap concealing what may still have been the same shock of

artificial blonde hair as in his other candid senior year photos. Here, even in

this close-up his posture is obvious, powerful but relaxed, conjuring an

uncomplicated stoicism that’s upstaged and undermined by the extraordinary

noise inside his eyes. You can’t listen, you can only look closer, through a

magnifying glass or a chem lab microscope, and then you’d see the cosmos as

through an observatory telescope, the traffic jams of planets, galaxy clusters

giving chase, collision, and rebirth after rebirth; the upset of orbits, an

impossible turbulence of color, all frozen in time, incorporated, and composed

without a blur. A

Venezuelan immigrant who came to this country with his family as a toddler,

Joaquin would have graduated from Marjorie Stoneman Douglas only a few months

after that day at the beach. Just

a year earlier when he and his family finally became United States citizens.

Joaquin wasted no time in exclaiming on Instagram : “Mama, we made it!”

I

can only stare, the cogs and wheels of my brain slump over, melted like a

Salvador Dali nightmare. I stare, like he’s an equation I lack the capacity to

solve, yet everything hinges on the solution. I’m determined, possibly programmed

to scour for answers, for patterns and truths. It’s a futile chase. All I see

is a handsome, much loved young man who can’t possibly know that within a

matter of days his dreams and plans, his secrets, his volumes of stories and

the quiet wildness in his eyes, will be obliterated. And

like those who’ve gone before him, Hadiya Pendleton, the 15 year-old honor

student who performed with her high school band at President Obama’s second

inauguration; Danny Parmertor, a 16 year-old Ohio student whose brother said

“would have changed the world;” 6 year-old Noah Pozner, one of twenty 1st

graders gunned down in Newtown who, like Joaquin, will exist only as a finite

photograph for the rest of his twin sister’s life just to name a few of the

tens of thousands of Americans extinguished each year to appease the

insecurities of craven open-carry lunatics Joaquin’s death will not be

necessary. It won’t be an unavoidable crash or a speeding meteor that’s

impossible to dodge. It will be senseless, and it will ripple outward wounding

everything it touches. Reasons? There are more than a few, all twisted into one impossible knot. Take them to a chem lab and boil them down to their single most prominent element, and you’ll never guess what you'll find: $$$$$

“Look at where the profits are, that’s how

you’ll find the source…. They’re gonna make a pretty penny, and then they’re all going to hell.”

-----Ani

DiFranco Does the fragility of life, the impudent, indiscriminate slaughter we’ve come to witness daily ultimately elevate and strengthen our perception of this human existence, or does the constant worldwide onslaught diminish it, reducing us equally to the status of animals? If he exists, God has proven that he doesn’t play favorites. No one is exempt. Whether it be church congregations mowed down by radicalized bigots or wedding guests perishing at the hands of an uninvited suicide bomber, the senselessness takes a heavy toll not just on our identity, but on our perception of reality itself. Culture is not a static concept. It’s in constant yet subtle flux, but we humans are remarkably skilled at adapting, particularly if our survival hinges upon it. Since the 2016 election, more than a few of my friends and family, as well as waiting room strangers, train passengers, checkout-line customers, a diverse sampling of 21st Century Americans with whom I’ve spoken when not eavesdropping, have admitted to either temporary abstinence from all forms of news and social media or, on the understandable extreme, an unyielding and permanent renunciation from the miracle of unlimited data for the sake of their survival, their psychological and physical wholeness. But

fortitude of that caliber is anything but abundant among our species and

eventually we cave to our curiosity, to our gluttony for undeserved punishment.

Exhausted, we flop down and adapt to life inside a warzone. How many mornings

have you opened your laptop, your phone, your tablet, the television that

someone thought was ingenious to embed into your refrigerator, and you grimace

and gag through your daily news sites until you see it. You weren’t expecting

it. Mechanically, you stop. Once

you’ve seen it, it’s too late. You may have forgotten, but there to remind you

is that disingenuously drab headline that sprouts verbatim almost everywhere

exactly two days after only the most publicized incidents, the headline that

blasts a cold shockwave down your spine, makes your insides feel a hundred

pounds heavier and prompts your reasoning skills to call in sick. It’s

over twenty years old. but that headline triggers a sickening paralysis in

those who can’t click, scroll, or distract themselves fast

enough, as well as those who, like me, hover for a while, preparing, driven by

the need to know, the need to see and thereby attempt to make sense of the

senseless. By

now, I can’t help but wonder if we’ve all become collectively, uncomfortably

numb to that headline , its uninspired words, differing only in city

and state, pushed to the bottom of the page like a Montenegro prime minister by

the absurdity of Trump’s latest Twitter tantrum. These are the victims of the _______

_______ shootings. A

few months ago, when I first started dabbling with YouTube clips of Glee,

I came across the late Naya Rivera’s tribute to Corey Monteith, a major cast

member who had died of an overdose before the taping of the fifth season. After

a rapid, irreverent introduction, she stood before her fellow cast members and

began singing “If I Die Young,” a song that was new to me. Its lyrics invoke

implications of not only consciousness beyond death, but of a worldly

afterlife, a theory that in my Catholic school youth I’d have never questioned. It’s a heart-crusher of a song and a scene,

addressing an impenetrable mystery, a code I cannot crack. What does it mean to

die young for any reason? We take the future for granted, sometimes we’re

resentful, dreading everything. But what if your pulse, your breath, your

plans, all the love that stabs at your heart were suddenly annihilated, forever? What

can we glean, if anything, from death that will help demystify the mystery of

life? The

morning after the shootings in Parkland I was sitting in one of a long line of

swivel chairs facing the wall-to-wall mirror inside a generic mass-market men’s

barber shop, a place best described by a word that eludes me the harder I hunt

it down, but essentially it’s the opposite of “metro-sexual.” On

the television attached to the wall in the upper corner, news crews and anchors

and experts were covering the shootings rather than Trump’s daily b***h-fit. As

expected, someone in the shop launches their best Ann Coulter/ bayou backwoods

impression, one that I’m certain was never rehearsed. Lucky day: it was the old

man to my left. As frustrated as a first grader forced to finish an SAT test,

he huffed and mumbled while the unamused

stylist retreated to her safe place while mechanically clipping the remains of

his white hair. “Crazy!” he said, fidgeting in his seat, fumbling for a

foundation.. “Guns ain’t never killed nobody! You cain’t… like… arrgh.”

Quite the doctor of rhetoric, he was casting his reel over the side of

the boat hoping anything would bite, an argument or an agreement, an engagement

of any kind no matter how inarticulate his grumblings of indignation. I could

care less where he came from or why the violent loss of seventeen lives didn’t

bother him in the least. I simply basked in his frustration at being ignored. But

the reality he kept smothered beneath multiple layers of excuses spoke for

itself. This man was afraid. Not of becoming a victim, but afraid that after

this massacre, as has been the case after every gun massacre, a mysterious

deployment of ghosts, maybe, or a super-secret SWAT team composed of

genetically modified talking cats, someone, anyone, would be knocking on his door

later that day to seize all of his guns and firearm paraphernalia. And

the only fear more disabling? The fear that it would never happen.

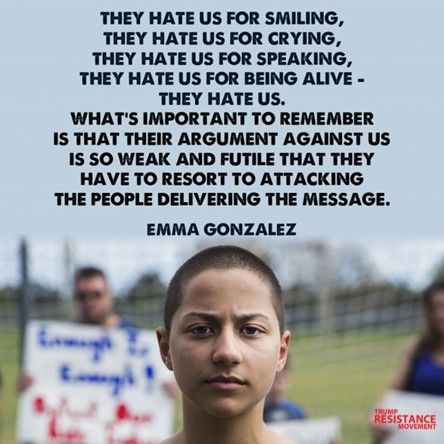

In

the aftermath of the massacre Emma Gonzalez, as well as her classmates who’d

narrowly survived the violence, became the heroes, the voices of righteous and

unswerving dissent to an exhausted, hopeless country that in the past, even

after the shootings at Newtown, the Pulse nightclub, and other schools,

mosques, temples, and churches from Texas to New Zealand, could do nothing but

pray, and even that proved useless once the world saw this latest handful of

student activists gathered around the oval office in front of the former

President, a stable genius who made no show of concealing the “How to be

Human” crib notes drafted just minutes earlier by a harried underling. And

the moneyed, hellbound ghouls of the NRA threw up their hands, licked clean of

blood, and in true Pavlovian fashion attacked their critics and anyone else who

dared threaten their heaping coffers, even a group of teenagers who’d narrowly

dodged a barrage of bullets in their own school while watching people they’d

known for years, if not most of their lives, fall indiscriminately all around

them. Shortly

afterwards that handful of survivors multiplied into the tens of thousands of

students who graduated overnight into demonstrators, protesters who walked out

of their schools despite authoritative repercussions. Emma organized the March

for our Lives protest where, upon taking the podium, she closed her eyes and

stood in silence, as did the rest of the sweeping crowd, for over six minutes,

the duration of the shooting spree at Marjorie Stone Douglas. If I

could afford to rent a reliable time machine, I’d love to be part of that

moment. I was so proud of them. I’d love to be the one to tell them that, in

the near future, as of this writing, the NRA has gone belly up and LaPierre,

last seen shooting elephants in what may have been the same poach-park

frequented by the Trump brothers, is praying for a new Texas home to a God he assumes

is rather fond of him. How

righteous and merciful would our world be if we could legally kidnap, tar. and

feather those b******s from the annals of recent history who’ve thwarted all

preventative gun violence legislation in a scheme to further enrich themselves

to such preposterous heights as to inspire comic relief to anyone who can’t

see, in broad shameless daylight, that they’re damned, soaked in the gleaming

blood and brain matter of tens of thousands of Americans who essentially died

for that express purpose, to sustain the luxurious lifestyles of a handful of

people whose names we’ll never know, who’ll never feel an inkling of remorse

whether or not they connect the dots.

Children are literally being shredded because

of their pocket-lining policies. Black men are shot to death in the back or in

department stores or park benches while these imbeciles emerge onstage to

thunderous cheers and applause at conservative conventions for the rifle they

hold above their heads en route to the podium, and anyone who objects or

protests such injustice is immediately labeled a terrorist. But

we know all about them, how they won’t listen, they won’t change. We’re assured

by our journalists and bloggers and maybe a few congressional leaders that

history will condemn them by way of Matthew Hopkins or Cotton Mather and that

there will come a time, assuming the human race survives to produce future

generations, when every school-kid will groan, boo, or hiss at the sound of

their names.

Utter bullshit. Nobody will remember their names, assuming this planet

will still accommodate lifeforms that remember anything. It’s

not a crisis that’s unique to America. Ordinary citizens, especially in Central

America, are trapped, terrorized, and quite often gunned down should word of an

insurgent reach the acting authoritarian dictator, who won’t hesitate to order

the entire family of a single dissenter executed. Someone lecture the good

pastor about that. So

parents, after weighing the odds, decide that a sweltering cross-country trek

by any means necessary is safer than staying at home, because no matter what

these terrified children find once their stowaway train grinds to a stop across

Mexico’s northern border, nothing could be worse than the death and rubble of

their homeland. The

United States is their only hope. And Donald Trump, after an illustrated crayon

briefing prepared by his Legion of Doom from their headquarters beneath the

muck of an un-drained swamp, not only sabotaged that hope but turned it into a

nightmare. But

somewhere, possibly in Two-Corinthians, it is written: “Suffer the little

children, and forbid them not to come to me.” Delighted, the Trump

administration and its task force dismissed the second half of that verse and

built concentration camps and enforced policies that knowingly, forcefully, and

shamelessly separated hundreds of children from their parents, some

permanently. “Bad hombres,” our former President

Spanglish’d at us. Meanwhile, his supporters desecrated Jewish cemeteries, pissed

on homeless people, and murdered their civilian political enemies by plowing their

cars into crowds of protesters. A couple of years ago, when the violence and destruction of Aleppo was making international news, one publication ran a chilling, illustrated piece covering one by one the stories of five Syrian children who sustained fatal injuries from bombs, shrapnel, or poisonous gas while inside their own homes with their families. The first photograph showed a team of doctors surrounding a bloody, unconscious toddler, and that was all I could take. I signed off, veered away from that site like a car swerving to avoid a moose, or in my case, a gaping black hole of guilt.

Guilt for backtracking, rewinding, hoping to record over that sickening

image. Guilt over my cowardice, for fretting over my shattered comfort zone.

And of course survivor’s guilt of American privilege. Looking at those

photographs sparks a chemical reaction, that same equation that’s impossible to

solve, probably because there’s no answer. But

each time that blunt and tiresome headline surfaces amidst each aftermath, my

resistance clicks on, as does, in my own way, the need to approach the casket

and peer inside. Strangely enough, after the Pulse nightclub shootings my

research into the identities of the victims was aggressive and spontaneous, its

immediacy attributable-- I’m guessing-- to my being a gay man, and I mourned,

paced in frustration, concentrating on what they must have been thinking: “Why

me? What did I do?” My

cursor hovers over the headline like an airplane circling in search of a

parking space. My resistance, under the guise of good sense, suggests I do some

pull-ups, maybe catch up on my digital comics subscriptions. I ask myself, my

bad but common sense, what the hell I expect to glean from this. I have to prepare,

to make sure; already I’m trembling. When it’s time I just go for it, wishing

instantly that I hadn’t.

Within seconds I’m face to face Joaquin Oliver for the first time.

--Roy Zimmerman For many

of us, home life during our teen years was often one sponsor short of a cage

match, but for Joachin, his mother was “his rock,” which is why I think of him

each time I hear the first verse:’ Lord, make me a rainbow The

song, however, blurs the lines between life and death, heaven and earth. In our

haste to exact justice, restore equilibrium while trapped inside America’s

hopelessly impossible gun culture, we find comfort in believing that the

victims were compensated with eternal peace and joy, as we would with any

departed loved ones. I

still hold on to a sliver of such hope even though I’ve gravitated toward

“non-believer” status. When those that I hold dear begin to pass, I’ll no doubt

adopt the same fallacy, that they’re dead but alive in the paradise that Jesus

promised. No hassles, no stress, no worries. No change, no growth, no

purpose.

Believe what you will believe. I

don’t know what to believe. And

should we disagree, we’ve amassed enough evidence in social sciences these past

few years to at least walk away with a few ounces of common ground, which

doesn’t amount to a hill of baked beans if one party lapses into the

convenience of psychotic denial. For years, they’ve believed with all the

passion of a religious fanatic that no, it’s a not a sleazy NRA slush fund

scam, the government really is coming for everyone’s guns. Oh, what the... "HOT

DAMN the black guy’s gone. Now there ain’t nothin’ in Washington except old

greedy white slobs and young greedy white bimbos. My guns are safe!"

Immediately, the NRA started hemorrhaging cash.

Once, I was a believer. But

inevitably, hard arctic logic crashed like a fallen tree in the middle of my

road to Mass, and now I can do nothing but marvel at the horror, the

unapologetic unfairness coursing like dark matter through the human experience.

If this consciousness and this world are all we have, there’s no greater

abomination than robbing someone of their life, thus robbing others of the

chance to say goodbye and still others the opportunity Like all of us, the odds of Joaquin ever entering

existence in the first place were one in 400 quadrillion. And

that infuriates me more than anything. The atrocity of an eager young life

exterminated and left to die where it fell. There’s nothing I can write about

him, or Cassie, Rachel, or Trayvon or Danny or anyone that will do them

justice; the best I’ve got is that this did not have to happen. They did not

have to fund Joe the Plumber’s pathetic weakling firearms fetish with their

lives, nor did their friends, families, and those victims who survived, all of

whom will suffer trauma and loss for the rest of their days. But

there’s one thing I found that I still keep, that shatters the barricades of my

cynicism and hopelessness, reminding me that my responsibility isn’t to grieve

over or dwell upon the world’s brutality but rather, for the time being, to

know where I stand and who I’ll stand up for. And what I found is a photograph

from an article I came across about two years ago, one that I bring up when I

lose perspective, when misanthropy sweeps like a disease through my good sense,

swift on convincing me that it is my better sense. The Syrian refugees photographed here have survived a dangerous, horrifying journey and, miraculously, have landed on the island of Lesbos where they are welcomed, even physically lifted onto steady ground by Greek military and volunteers.

It’s over,” the boy is thinking. Although they’ll face plenty of new hardships upon setting foot on land, this moment captures the end of by the longest but hardly the cruelest trauma they’ve survived. They’ve lost their homes, their friends and family, their possessions and their identities everything except each other. A kaleidoscope of a hundred congested emotions converges through the boy’s tears; that they are hated, that people they’ve never met want them dead for reasons that have nothing to do with anything they’ve done, how could the probability of death not proven welcoming? He can’t believe they survived, that, although they were left with nothing, hope prevailed. It’s over. It’s just beginning.

“We’re safe,” his disbelief veering into shock. “It’s

over. We made it.” And if I hear one more

time about a fool’s right to his tools of rage, I’m gonna take all my

friends, and we’re gonna move

to Canada, and we’ll die of old

age.

--Ani DiFranco “To the Teeth”

© 2021 Seth CasonFeatured Review

Reviews

|

Stats

134 Views

2 Reviews Added on September 14, 2021 Last Updated on September 14, 2021 Tags: School shootings, Firearms, Politics, Parkland AuthorSeth CasonAlexandria, LAAboutHumble, aspiring, and highly frustrated writer with no affinity toward or aptitude for computer-ism-- although I'll choose MS Word over a typewriter any day, thank you. See?-- Humble. Along with poetr.. more..Writing

Related WritingPeople who liked this story also liked..

|

Flag Writing

Flag Writing