Riding the Red LineA Story by Ed StaskusRiding the Red Line

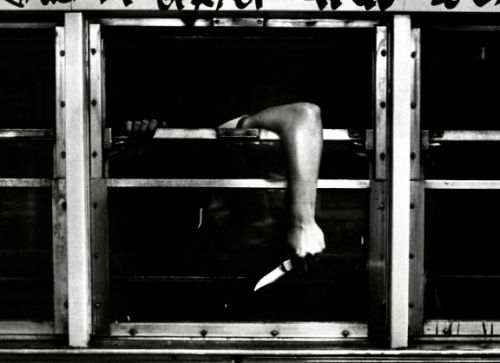

By Ed Staskus The last summer we lived in the immigrant neighborhood around Eddy Rd. was the last year my friends and I took Cleveland’s Rapid Transit train downtown many Saturdays to mess around and go to the movies. It was 20-some years since the city-owned train system got a move on. It was 1963. The newspapers were all about civil rights and Vietnam, two issues we barely knew anything about and cared about even less. What we cared about was whatever was right in front of our eyes. Stevie Wonder released his first live album, “The 12 Year Old Genius,” in 1963. We were all 12 and 13 years old. None of us were geniuses, not by a long shot, although some of us went on to be able to think more or less clearly. Push-button telephones were new, first class postage cost five cents, and President John F. Kennedy visited West Berlin, delivering his famous “Ich bin ein Berliner” speech. We went around calling each other Berliners and saluting Nazi-style. All of us had voted for JFK in a mock election at St. George’s Catholic School. Our nuns told us to stop saluting and pay attention to JFK’s good deeds, but they need not have. He was young, energetic, and handsome, while Richard Nixon was a shifty old man with a five o’clock shadow. The CTS Rapid Transit was a light rail system, what we called a wagon train. Tens of millions of riders rode it every year, especially on Saturdays, when it seemed like all of them were riding it at once to go shopping downtown. We had to stand most of the time. Even when we got a seat, we had to give it up to pregnant women, crippled men, and old folks. Standing and swaying and holding on to a pole didn’t matter. We were excited about roaming around downtown and seeing a big-time movie. All we had known in our earlier years was the neighborhood Shaw-Hayden Theater, which we could walk to. They showed monster movies, cowboy movies, and rocket ship movies on Saturday afternoons. Cartoons and a double bill cost 50 cents. We ignored the newsreels. Popcorn cost 15 cents, but since we were chronically short on hard cash, we brought our own in brown paper bags hidden under our jackets. Sometimes we stopped at Mary’s Sweet Shoppe and bought some penny candy. There was a playground behind the local fire station with Saturday Sandbox contests, but we never went, being too old for sandboxes. There were dances at the Shaw Pool every Saturday night, but we never went to those either, being too young to know much about girls. Before the movie matinee there was sometimes a drawing for prizes. One of my friends won two thousand sheets of paper one winter afternoon. He was beside himself hauling the reams home in the snow. He complained about frostbite, but he was a whiner at school, so we ignored him. The theater was big, more than a thousand seats. We usually went early so we could sit in the front row, stretching our legs out, horsing around, kicking each other, and whooping it up during the movie. Going downtown meant hoofing it from where we lived off St. Clair Ave. down East 128th St. to Shaw Ave. to Hayden Ave. and following an unnamed unmapped foot path to the Windermere station. We scrambled up the embankment, crossed the tracks at the rear of the station, and waited on the platform for the downtown bound train. Windermere was the end of the line for the Red Line. The Red Line ran at ground level, alongside railroad rights-of-way. There are no grade crossings with streets or highways. All of the stations along the way had high platforms. Unlike most transit lines, it was powered by an overhead electric catenary instead of a third rail. When the steel wheels finally rolled into the underground station in the city center we dusted ourselves off and ran upstairs, running through the Terminal Tower lobby and bursting outside, rain or shine. We made tracks around Public Square until there was nothing left to see. We liked walking to the movies on one of the three main avenues, which were Prospect, Euclid, and Superior. Our parents warned us to stay away from Prospect Ave., where there were prostitutes and burlesque houses. It was because of their words of wisdom that we took Prospect Ave. most of the time, although we never talked to the hookers and never went into the bars and strip clubs. We weren’t interested in smut, and besides, we wouldn’t have been able to pay for the cheap thrills. All the money we had we hoarded for the train, the movie, and snacks. There were five theaters clustered between East 14th and East 17th. Four of them faced Euclid Ave. while one faced East 14th St. The three blocks were known as Playhouse Square, although none of us knew that. We didn’t pay attention to signs unless they had something to do with food or the movies. All of us had our own money, cobbled together from allowances, paper routes, altar boy service at weddings, and even thievery from our siblings if push came to shove and our Saturday was threatened. The Ohio and State theaters were built by New York City plutocrat Marcus Loew in the early 1920s, followed by Charles Platt’s Hanna Theater. The Hanna was named for Mark Hanna, Cleveland’s wheeler-dealer senator in Washington. The Pompeiian-style Allen Theater opened at about the same time. The last theater opened at the end of the next year in the Keith Building, the tallest skyscraper in the city at the time. The biggest electric sign in the world was fabricated and turned on the night of the Palace Theater’s opening. The movie house was billed as the “Showplace of the World.” The opening night entertainment was headlined by a famous mimic and featured dancing monkeys. Everybody said it was “the swankiest theater in the country.” It wasn’t swank anymore when we started going to Saturday matinees, but we didn’t notice the wasting away. It had wide seats and a gigantic screen and that was all that mattered. The movies cost 75 cents and we were glad to pay it. It was where we saw “Son of Flubber” and afterwards pretended to defy gravity like Fred MacMurray. We saw “It’s a Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad World” and laughed until we cried. We loved stories about lost treasure. It was perpetual motion and shouting. Ethel Merman was the most likable loudmouth we ever heard. We saw it three times and it seemed new every time. We saw “Cleopatra,” but agreed afterwards that we had all gotten sick of Elizabeth Taylor. “Why is she even in the movie?” we wondered. Rex Harrison and Richard Burton were more like it. Thousands of Romans with spears and shields fighting each other was even more like it. Sandals and swords in action were what we had paid to see. We wanted to see “Psycho” but weren’t allowed. We were warned it was too intense and inappropriate for boys our age. We were offended, but when we heard what it was about, we asked each other what all the fuss was. It sounded like a sicko stabbing people, which was right up our alley. We had all seen plenty of horror movies, like “Carousel of Souls” and “Village of the Damned.” When “The Raven” was playing we saw it right away, even though none of us knew Edgar Allen Poe from the Man in the Moon. There’s a black bird. There’s a tapping at the door. The night is dark and the wind is howling. When the door is opened there’s nobody there. “Watch your back!” we shouted at the screen. The Big Three in that movie were Vincent Price, Boris Karloff, and Peter Lorre, even though Peter Lorre was a midget. He had a sinister voice, hooded eyes, and a dodgy way about him, which made up for his lack of height. Vincent Price was disappointing, although he was the tallest. He spoke and acted like a sissy Gentleman Jim, even though he was supposed to be a big bad magician. In the end the whole business was disappointing. It was more funny than scary, and once we realized how it was going, we enjoyed it for the laughs. The Big Three turned out to be the Three Stooges in disguise. We took a chance and asked for our money back, claiming intense disappointment, but a grouch in a blue suit ushered us out and told us where to go. We heard about “Seven Wonders of the World” on WERE-AM radio before we ever saw it on the marquee of the Palace Theater. We didn’t go see it, even though we saw it on the marquee week after week and even though it was in Cinerama. We saw everything in Cinerama, anyway, since we always sat in the front row. A wide screen always made a bad movie twice as good. Our real life hometown was where we went to see the wonders of the world. We wandered around in the Flats amazed, stargazing up at the steel plants, looking down on the greasy Cuyahoga River, watching the up and down bridges go up and down as freighters hauling ore slowly made their way upstream. Six years later the river caught on fire, flames and plumes of black smoke turning day to night. We walked along the shoreline of Lake Erie where fishermen pulled perch and walleye out of the dirty water that nobody was supposed to swim in. We snuck into Municipal Stadium, called the Mistake on the Lake, whenever we knew the fire-balling lefty Sam McDowell was pitching. He was 20 years old and tall as a tree. Hardly anybody went to see the back of the pack team and we often had most of the 80,000 seat stadium to ourselves, cheering on the Tribe. When ushers asked to see our ticket stubs, we hemmed and hawed and changed sections. Whenever we ended up in the bleachers there were never any ushers to roust us. If it was hot, we pulled our shirts off. We threw popcorn to the pigeons and pebbles at them when they were finished with their free goodies. The movies were magic to us. They were like a dreamland in waking life. It didn’t matter if the story was real or unreal. We were dazzled by the moving images and the music. It was disorienting coming out of a dark auditorium after a matinee into bright sunlight, like after a midday nap when daydreams had come fast and furious. The weekend before our summer vacation was going to be over and we had to go back to school, we saw our last movie at the Ohio Theater. It was “Lord of the Flies.” It was about boys our age who were marooned on a desert island. We thought we were experts about what constituted a boy’s life and didn’t know anybody who ever did what they did. We began to suspect movies were some kind of art form. We didn’t like grown-ups making up art about us. We appreciated great trash but not great art. All of us wrote it off as hokum with a message. We were instinctively wary of messages. Going home on the Red Line late one Saturday we saw a fight break out. Two men had been talking, then shouting, then shoving each other in the aisle, until one of them pulled a knife and stabbed the other one in the arm. Real blood gushed and stained his clothes. A woman screamed. Two men grabbed the knifer and held him down, while another man took his tie off and tied a tourniquet on the upper arm of the stabbed man. When we got to the Windermere station there were police cars and an ambulance there. We watched, fascinated, until a policeman told us to “break it up and go home.” We went home more breathless than any movie had ever made us. John F. Kennedy was shot and killed that fall, which put a pall over everything. A fire broke out in the Ohio Theater the next year and the other theaters were hit by vandalism. All of them closed between the summers of 1968 and 1969 except for the Hanna. We were juniors and seniors at St. Joseph’s High School by then and the only movies we went to were at the LaSalle Theater in our North Collinwood neighborhood. But by then when we went to the movies we were more interested in girls than whatever was playing, although we found out horror movies were the way to go. There was never any doubt about what to do with your hands when you were with your main squeeze and the scary parts started. Ed Staskus posts monthly on 147 Stanley Street at http://www.147stanleystreet.com, Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com, Down East http://www.redroadpei.com, and Lithuanian Journal http://www.lithuanianjournal.com. To get the site’s monthly feature in your in-box click on “Follow.” Help support these stories. $25 a year (7 cents a day). Contact [email protected] with “Contribution” in the subject line. Payments processed by Stripe. “Bomb City” by Ed Staskus “A Rust Belt police procedural when Cleveland was a mean street.” Sam Winchell, Beyond Fiction Cleveland, Ohio 1975. The John Scalish Crime Family and Danny Greene’s Irish Mob are at war. Car bombs are the weapon of choice. Two police detectives are assigned to find the bomb makers. Nothing goes according to plan. A Crying of Lot 49 Publication © 2025 Ed Staskus |

StatsAuthorEd StaskusLakewood, OHAboutEd Staskus is a free-lance writer from Sudbury, Ontario. He lives in Lakewood, Ohio. He posts on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybo.. more..Writing

|

Flag Writing

Flag Writing