Elbow GreaseA Story by Ed StaskusElbow Grease

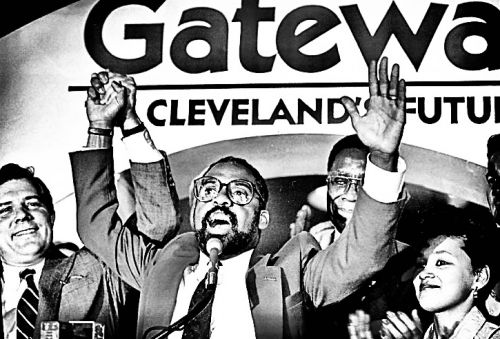

By Ed Staskus When Mike White was elected the 55th mayor of Cleveland in the fall of 1989 he became the city’s second youngest mayor. Everybody thanked their lucky stars he wasn’t Dennis Kucinich, who had been the youngest, and who had bankrupted the city in 1978. He also became the city’s second African American mayor. Blacks weren’t exactly Blacks then, although they were getting there. They were African Americans. When Frank Jackson finally retired in 2022, after serving four terms as the 57th mayor of Cleveland, Mike White became the second-longest-serving mayor. He had served three terms. The day he was sworn in he inherited a boatload of crime, poverty, and unemployment. The tax-paying population of the city was shrinking fast. Downtown was more a hotbed of boll weevils than hotties. There was no Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and no Gund Arena, which is now Rocket Mortgage Field House. The Indians and Browns were both still playing their ballgames in the decrepit Municipal Stadium on the south shore of Lake Erie, although the Browns were thinking of packing up and moving to Baltimore. My wife and I were living in Lakewood, which wasn’t Cleveland, although it was close enough. It was the big city’s next door neighbor, what in the day was called a streetcar suburb. Nearly half of Cleveland’s residents were African American. Less than 1% of Lakewood’s residents were African American. We lived on the west end of town where there were zero African Americans. There wasn’t a Berlin Wall keeping them out of town but there was a Berlin Wall. We lived off Riverside Ave. on the east side of the Rocky River valley, which had been transformed into the Rocky River Metropark. The river and the valley were just steps from our front porch. Cleveland’s racial divisions seemed like a distant problem. In the event, one day a man was apprehended throwing more than a dozen black bowling balls into the Rocky River at Eddys Boat Dock. He explained to the police officers, “I thought they were n****r eggs.” Being the mayor of a village is hard enough. Being the mayor of a city can be thankless. It can be worse than thankless when the top dog shows up. “I would not vote for the mayor of that town,” Fidel Castro once said while touring his island nation. “It’s not just because he didn’t invite me to dinner, but because on my way into town from the airport there were such enormous potholes.” There was only one reason Mike White wanted the job. He was a born and bred Cleveland man. He was a true believer and a do-gooder. He was bound and determined to make the city a better place to live. “I remember looking out at the crowd of Cleveland residents, black and white, and reflecting on how many children were there,” he said about his inauguration day in 1990. “I remember how they looked at me as a symbol of what could be. It speaks to the powerful responsibility of being the kind of leader people want to follow.” Getting the job done was going to be a problem, if not Mike White’s man-sized burden. He presented himself on the stump as pro-business, pro-police, and an effective manager. He argued that “jobs are the cure for the addiction to the mailbox,” by which he meant once-a-month welfare checks. He didn’t win over any live and die by the mailbox voters. In the end he won 80% of the vote in the white wards, 30% of the vote in the African American wards, and 100% of the brass ring. “Caesar is dead! Caesar is dead!” the crowd in Cleveland Centre cheered when the result was announced. It was near midnight. “Long live the king! Long live Mike!” When the mayor-elect appeared, people stood on chairs and cheered some more. “I extend my hand to all of Cleveland whether they were with me or not” he said. It had been a bitter uphill campaign. “The healing begins in the morning!” There were more cheers. “We … shall … be… ONE … CITY!” He spent twelve years trying to make it happen. “Winning an election is a good-news, bad-news kind of thing,” Clint Eastwood, the movie star who was once the mayor of Carmel-by-the-Sea, has said. “Okay, the good news is, now you’re the mayor. The bad news is, now you’re the mayor.” He ran on a promise to roll back Carmel’s back-handed ban on ice cream cones. The law stated that take-out ice cream cones had to be in secure and foolproof packaging with a cover. “Eating on the street is strongly discouraged,” the suck all the fun out of it city fathers said. The actor beat the incumbent in a tight race. One of his first official acts was getting au naturel ice cream cones back on the streets. After his two-year term was over he never stood for elected office again. Politics was too dirty for even Dirty Harry. By the time Mike White took office I couldn’t have cared less about Cleveland. For one thing, I no longer lived there anymore. For another thing, I wasn’t working in Cleveland anymore. I was working for the Light Bulb Supply Company. They were in the Lake Erie Screw Building in Lakewood. I wasn’t attending Cleveland State University anymore, either. As much as I used to go to the asphalt jungle was as much as I didn’t go there anymore. The city in 1990 was a mess, literally. Nobody thought anything about throwing litter and trash into the street. The police had never been busier. The fire department had never been busier. The schools had deteriorated so much that everything educational looked like up to the teachers. The graduation rate was less than 40%. “It couldn’t have gotten much worse,” recalled James Lumsden, a school board member. Mike White likened the schools to the Vietnam War, where well-meaning people went to help, but ended up stuck in a nightmare. Manufacturing jobs were disappearing, the workforce hemorrhaging paychecks, labor costs being outsourced like nobody’s business. Only street cleaners felt secure in their employment. The No. 1 bank in the city, Cleveland Trust, which had become AmeriTrust, was being dragged down by bad loans and a collapsing real estate market. The iconic May Company was drawing up plans to close its downtown store, which had been on Public Square for nearly 90 years. In 1950 the city was the 6th largest in the country. Forty years later it was the 23rd largest in the country. Everybody who could move away was moving to the suburbs. When the inner ring suburbs filled up, new outer ring suburbs popped up. When they filled up, exurbia became the next place to go. Nobody from nowhere was moving to Cleveland. It was hard to believe anybody wanted to be mayor. Mike White grew up in Glenville on Cleveland’s east side. It was a rough and tumble neighborhood, notorious for a 1968 shootout. Gunfire was exchanged one night for nearly four hours between the Cleveland Police Department and the Black Nationalists of New Libya. They were a Black Power group. Three policemen, three Black Power men, and a bystander were killed. Fifteen others were wounded. Lots of others were shoved into paddy wagons and locked up. The new mayor’s father was a machinist at Chase Brass and Copper. He was a union man and ran a union shop at home, too. “If not for the discipline at home, we would have been lost,” Mike’s sister Marsha said. The first summer Mike White came home from college in 1970 his father took one look at him and told him to cut his hair. He had grown it long and was fluffing it into an afro. While he was a student at Ohio State University in Columbus he protested against racial discrimination practiced by the capital city’s public bus system. He was arrested. He got involved with Afro-Am and led a civil rights protest march. He was arrested again. The charges were disorderly conduct and resisting arrest. He didn’t deny the charges. “I hated the sheets back then,” he said. He was sick and tired of being arrested. He put his thinking cap on and ran for Student Union President. When he won he became Ohio State University’s first African American student body leader. He earned a Bachelor of Arts degree in 1973 and a Master of Public Administration degree in 1974. He began his professional political career as an administrative assistant for Cleveland’s city council in 1976 and was elected councilman from the Glenville neighborhood in 1978. From 1984 until he ran for mayor he represented Ohio’s 21st District in the State Senate, serving as assistant minority whip for the Democrats. Mike White’s opponent in the race for mayor was the long-time politician George Forbes, who was also African American. The color of his skin turned out not to matter. Mike White had gone color blind. He described George Forbes as a “foul-mouthed, uncouth, unregenerated politician of the most despicable sort.” The Forbes campaign countered by accusing their opponent of abusing his wife and abusing the tenants of his inner-city properties by ignoring housing codes. The difference between a hero and a villain can be as slight as a good press agent. I didn’t pay too much attention to the character assassinations. My wife and I were working on our new house. It had been built in 1922, and although the previous owners had done what they could, it was our turn to do what we could. What we were doing first was ripping out all the shag carpeting and taking all the wallpaper down. When we were done with those two projects we painted all the walls and restored the hardwood floors. Our game plan was by necessity long-term. We started on the basement next, started saving for a new roof, and started making plans for everything else. Mike White didn’t give a damn about ice cream cones, but he gave a damn about the kids who ate ice cream cones. “We can spend our money on bridges and sewer systems as we must,” he said, “but we can never afford to forget that children remain the true infrastructure of our city’s future. We need to create a work program and show every able-bodied person that we have the time and patience to train them. And we should start people young. We want to guarantee every kid graduating from high school a job or a chance to go to college.” He put the city’s power brokers on notice. “We do not accept that ours must be a two-tier community with a sparkling downtown surrounded by vacant stores and whitewashed windows. You can’t have a great town with only a great downtown. I’ve said to corporate Cleveland that I’m going to work on the agenda of downtown, but I also expect them to work on the agenda of neighborhood rebuilding.” He wasn’t above making deals, although he wasn’t selling any alibis. Safety became a mantra for him. “Safety is the right of every American,” he said. “A 13-year-old drug pusher on the corner where I live is a far greater danger to me and this city than Saddam Hussein will ever be.” He would prove to be true to his commitments. In the meantime, he put his nose to the grindstone. He worked Herculean hours. His staff worked Herculean hours. Anybody who complained they weren’t Hercules was advised to find work elsewhere. When he found out the Gulf War was costing the United States $500 million a day, he was outraged. “I’m the mayor of one of the largest cities in the country while we have an administration in Washington that is oblivious to the problems of human beings in this country,” he said. “I sit here like everyone else, watching CNN, watching a half-billion dollar a day investment in Iraq and Kuwait, and I can’t get a half-million dollar increase in investment in Cleveland.” Mike White was never going to be president of the United States. He probably didn’t want to be president. He had his hands full as it was, making it happen in his hometown. He wanted a Cleveland with dirtier fingernails and cleaner streets. The city was in a hole. His goal was to get it to stop digging. It wasn’t going to be easy. He didn’t always speak softly, but words being what they are, he made sure that as mayor he carried a big stick, the biggest stick in sight. He was going to need it, if only because President Lyndon Baines Johnson had said so. “When the burdens of the presidency seem unusually big, I always remind myself it could be worse,” LBJ said during his troubled administration. When asked how that could be, he said, “I could be a mayor.” Ed Staskus posts on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. © 2023 Ed Staskus |

StatsAuthorEd StaskusLakewood, OHAboutEd Staskus is a free-lance writer from Sudbury, Ontario. He lives in Lakewood, Ohio. He posts on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybo.. more..Writing

|

Flag Writing

Flag Writing