Dark CityA Story by Ed StaskusDark City

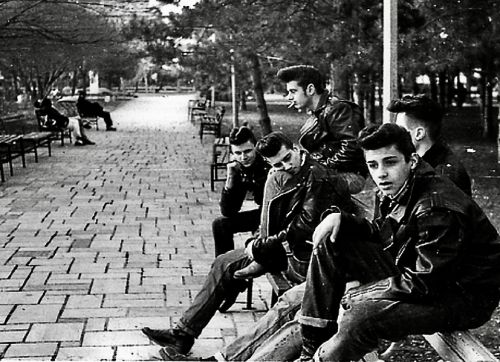

By Ed Staskus When Stan Riddman took the stairs two at a time up from the basement of the Flatiron Building it wasn’t a dark city, yet. The new night was still on its way. The sky was a hazy lemon and smoggy blue. It was the first day of the second week of fall, but felt more like the middle of summer, except for the shorter autumn days. Stan wore a short sleeve shirt and linen trousers. The wallet in his back pocket was flush with more fives and tens than it was with its usual one-spots. He gave the leather a friendly pat. The seven-card stud he had played in the dingy room next to the furnace room had been good to him. I can buy the kid some new clothes, get up front on the office rent, and score tickets for the Series, he thought. The Socialist Labor Party used to have offices in the Flatiron Building, but not down in the basement. They thought they were in the cards back then. They didn’t know they were shooting snake eyes. He wondered if they would have banned gambling, making it out like it was exploitive, if they had ever come to power. You took your chances at poker, but it was only exploitive if you had no skill at it. You deserved to be taken if you played dreamland. Stan never shot craps. He never put himself at the mercy of cubes of white resin bouncing around at random. He walked down 22nd Street to Lexington Avenue, turned right, walked through Gramercy Park to Irving Place, and looked for a phone booth. The big day was coming up fast. The Yankees were in, and the Indians were out, that was for sure. The Redlegs were running on an outside track. The Braves were neck and neck with the Dodgers. Sal the Barber had no-hit the Phils earlier in the week at Ebbets Field and the Cardinals were going hard at the Braves out in the boondocks. It was all going to come down to this weekend as to whether there was going to be a subway series, the same as last year, or not. Last year’s Fall Classic went seven games, and the quirky thing about it was the Yankees won their three games at Ebbets Field and the Dodgers won their four games at Yankee Stadium. Neither team won on their home field. Nobody had taken that bet because it wasn’t in the cards. Nobody took the backside odds on the seventh game, either, especially since Jackie Robinson wasn’t penciled in to play the deciding nine innings. At least, nobody but Stan and Ezra, and anybody else who flipped a coin. Who would have thought the Cuban would be the difference-maker in the deciding game when he took over right field in the sixth inning last year? Stan was in the upper deck with his sometime partner, Ezra Aronson. The Yankee dugout was on the first base side, so most of the Bum fans were on the third base side. A client who was a Yankee fan, after Stan had gotten him the black and white proof he needed to get his divorce done, gave him a pair of passes, so they were on the wrong side of the rooting section. “Beggars can’t be choosers,” Ezra said, sitting in a sea of Bronx Bomber fans. When Yogi Berra hit an opposite field sure-fire double, Ezra sprang out of his seat, like everybody else, but the lightning-fast right fielder Sandy Amoros caught it coming out of nowhere. He fired a pill to Pee Wee Reese, who relayed it to Gil Hodges, who doubled up the retreating Gil McDougald off first, ending the last threat Stengel’s Squad made that afternoon. Casey Stengel managed the Yankees. Back in his playing days, when he still had legs, he had been a good but streaky ballplayer. Fair bat, good feet, great glove. “I was erratic,” he said. “Some days I was amazing, some days I wasn’t.” When he wasn’t, he played it for laughs, catching fly balls behind his back. One afternoon he doffed his cap to the crowd and a sparrow flew out of it. Another day, playing the outfield, he hid under the grate of a storm drain and popped out of the drain just in time to snag a lazy fly ball. Whenever he stood leaning over the front top rail of a dugout, he looked like a scowling Jimmy Durante and a sad sack Santa Claus dressed up in pinstripes. He was called the Ol’ Perfessor, even though he had barely gotten through high school. He managed the Braves and Dodgers for nine years and chalked up nine straight losing seasons. Casey Stengel might not have been a for-real professor, but he knew enough not to give up. After the New York Yankees hired him in 1948, the only year he hadn’t taken them to the World Series was 1954. Stan and Ezra were the only men in their section who had not fallen back into their seats, stunned, after the Cuban snagged Yogi Berra’s liner. Stan had to pull the cheering Ezra down so there wouldn’t be any hard feelings. As it was, Ezra was so excited there were hard feelings, after all, and Stan had to drag him away to a beer stand. “This beer is bitter,” Ezra scowled, looking down at the bottle of Ballantine in his hand. Ballantine Beer was featured on the Yankee Stadium scoreboard, its three-ring sign shining bright, flashing “Purity, Body, Flavor.” Whenever a Yankee hit a homer, Mel Allen, the hometown broadcaster, hollered, “There’s a drive, hit deep, that ball is go-ing, go-ing, gonnne! How about that?! It’s a Ballantine Blast!” The Brooklyn Dodgers, Ezra and Stan’s home borough team of choice, played at Ebbets Field. Their scoreboard boasted a Schaefer Beer sign, with the ‘h’ and the ‘e’ lighting up whenever there was a hit or an error. Below the beer sign was an Abe Stark men’s wear billboard. “Hit Sign, Win a Suit”. “That’s some super beer, that Schaeffer’s,” said Ezra, half finishing his bottle of Ballantine. “The Yankees don’t know good beer from spitballs.” He threw the bottle towards a trash can. Stan Riddman didn’t have a home borough, even though he favored the Bums. He had an apartment in Hell’s Kitchen, up from Times Square and down from the Central Park Zoo. He wasn’t from New York City. He was from Chicago, although he wasn’t from there, either. He had been born in Chicago, but when his mother died two years later, in 1922, his father moved the family, himself, a new Polish wife, two boys, two girls, two dogs, and all their belongings a year later to a small house behind St. Stanislaus Church in Cleveland, Ohio. It was in the Warszawa neighborhood south of the steel mills, where his father ended up working the rest of his life to provide for his family. Stan worked in the steel mills for three years while still living at home. He volunteered for the armed forces the minute World War Two started. He wasn’t working on anything at the moment that he thought might get him free Series passes this year. As long as I put most of this away, he thought to himself, walking down Irving Place, thinking of the jackpot in his pocket, I can blow some of it tonight, and still have enough for ballgames and some more card games. Stan had stopped being his father’s son long ago. His daughter Dottie was at Marie’s for the weekend. Marie had once been Stan’s wife. Her taking an interest in Dottie happened about as often as the Series. It wasn’t too early or too late, and if Vicki hasn’t taken any work home, and is at home, and picks up the phone, maybe she could meet him for dinner. He found the phone booth he’d been looking for and called her. It rang almost twice before Vicki answered. That’s a good sign, he thought. “Hello.” “Hey, Vee, it’s Stan.” “Stan, my man,” she laughed. “How’s Stuy the Town tonight?” he asked. “Hot, quiet, lonely,” she said. What Stan liked about Vicki was she didn’t talk about what didn’t matter. She wasn’t a sexpot, but she liked sex well enough. Marie had been romantic as a pair of handcuffs. Towards the end she had taken to waving a handful of razor blades at him. “How about meeting me at Luchow’s for dinner?” he asked. “I’m buying.” “Stan, I love you for the dear Polack or whatever you are, but the food at Luchow’s is not so good, even if you can ever get though that insanely long menu of theirs.” “That’s what I’m here for,” he said. “A sharp-eyed investigator like me will make sure to look into everything the kitchen’s got to offer and find what’s edible.” “More like dog-eared investigator,” Vicki said. “All right, but the other thing is, since they seat more than a thousand people, how am I going to find you? And if I do, with that strolling oompah band of theirs, if we do bump into each other and maybe get a table in that goulash palace, we’ll only be able to make ourselves heard some of the time and not the rest of the time.” “We can always take our coffee and their pancakes with lingonberry over to the square after dinner and chew the fat,” he said. “It will be quiet enough there.” “Chew the fat? What it is I like about you? Sometimes I just don’t know.” “I’ll take that for a yes.” “Yes, give me a few minutes to change into something fun,” she said suddenly gay. “I hope there’s no goose fest or barley pop festival going on.” “Meet me at the far end of Frank’s bar. He’ll find a low-pitched spot in the back for us. He says the new herring salad is out of this world.” “Don’t push your luck, Stan, don’t push your luck,” she said. Herring always made her feel like throwing up. Luchow’s was a three-story six-bay building with stone window surrounds, pilasters, and a parapet on top, while below a red awning led to the front door. The restaurant was near Union Square. It looked like the 19thcentury, or an even earlier century, dark heavy Teutonic, North German. A titanic painting of potato gatherers covered most of a wall in one of the seven dining rooms. Another of the rooms was lined with animal heads, their offspring being eaten at the tables below them, while another room was a temple of colorful beer steins. There was a beer garden in the back. “Welcome back to the Citadel of Pilsner,” said Frank. He gestured Stan to the side. “Did anybody tell you Hugo died?” “No, I hadn’t heard, although I heard he wasn’t feeling well,” said Stan. Hugo Schemke had been a waiter at Luchow’s for 50 years. He always said he wasn’t afraid of death. He had firmly no ifs ands or buts believed in reincarnation. “Did he say he was coming back before he left?” “He did say that, but I haven’t seen him yet,” said Frank. “How’s Ernst doing?” asked Stan. Ernst Seute was the floor manager, a short stout man both friendly and cold-hearted. He had been at Luchow’s a long time, too, since World War One. He was deadly afraid of death. “He took a couple days off,” said Frank. “Remember that parade back in April over in Queens? They’ve got some kind of committee now, and he’s over there with them trying to make it an annual thing here in Little Germany, calling it the Steuben Parade.” “You going to be carrying the cornflower flag?’ “Not me, Stan, not me.” Frank was from Czechoslovakia. “I’m an American now.” Frank led Vicki and Stan to a small table at the far end of the bar. He brought them glass mugs of Wurzburger Beer and a plate of sardines. Vicki ordered noodle soup and salad. “Hold the herring,” she commanded. Frank looked puzzled. Stan asked for a broiled sirloin with roasted potatoes and horseradish sauce on the side. “I saw Barney the other day,” Vicki said, cocking her head. “He told me you’ve made progress.” “I didn’t think there was anything to it the first day I saw him, that day you brought him over to the office,” said Stan. “I didn’t think there was much to it that whole first week at the top of the month. Then there was all that action, but Bettina finally got the business of it worked out, that it was the shrink. So, I know who did the thing to get Pollack to drive himself into that tree up in Springs. I know how they did it. What I don’t know is why they did it.” “Do you know who they are?’ “No, I don’t, even though one of the two small-fry, a sicko by the name of Ratso Moretti, who roughed up Ezra, is being held at the 17th. He doesn’t seem to know much, but what he does know says a lot. The head shrinker might be the key. He is going to tell me all about it soon, at least what he knows, and what he doesn’t know, too. He hasn’t gotten the news flash about the talk we’re going to have, yet, but that doesn’t matter.” “You don’t think Jackson Pollack had anything to do with it?” “He was the wrong man in the wrong place, that’s all, if you look at it from his point of view. Bettina and I think he was a test run. We think they’re up to something bigger. It’s hard to figure. It’s got to be big, but we can’t see the pay-off in it. You know Betty, though. She’ll piece it together if she has to tear it apart.” After dinner they looked at the dessert menu, but it was only a glance. Vicki shook her head no. “How about coffee and dessert at my place?” asked Stan. “We can stop and get pastry at that Puerto Rican shop on the corner and eat up on the roof.” It had become a clear night. The smog had blown away. “I can’t pass up that tasty-sounding pass,” said Vicki. They hailed a Checker Cab. “Take us up 5th to 59th, to the corner of the park,” said Stan. The cabbie dropped them off at the Grand Army Plaza and they walked into the park, following the path below the pond towards the Central Park Driveway and Columbus Circle. He liked Vicki’s breezy walk. They didn’t notice the two teenagers, as they quietly strolled down a wooded path south of Center Drive, until the two of them were in front of them, blocking their way. One was taller and older, the other shorter and younger, their jet black hair oiled and combed back. Both of the dagos were wearing high tops, jeans, and white t-shirts, one of them dirtier than the other. They had left their leather jackets at home. The younger boy, he might have been fifteen, had a half-dozen inflamed pencil-thick pencil-long scratches down one side of his face and more of them on his forehead. Small capital SS’s topped with a halo drawn in red ink adorned the left sleeve of his t-shirt. The taller boy had LAMF tattooed on his neck above the collar line to below his right ear. Stan knew what it meant. It meant “Like a Mother F****r.” He kept his attention fixed on LAMF’s eyes and hands. “Hey, mister, got a double we can have for the subway, so we can make it back home,” he asked Stan, smiling like a hyena, his teeth big and white as Chiclets. One of his front teeth was chipped. They were Seven Saints, JD’s whose favorite easy pickings was holding back the door of a subway car just before it was ready to leave the station, one of them grabbing and running off with a passenger’s pocketbook, while the other one released the door so the woman would be shut tight inside the train as it slowly moved away from the platform. Every Seven Saint carried either a knife or a zip gun for when the pickings weren’t easy. “Where’s home?” asked Stan, stepping forward a half step, nudging Vicki behind him with his left hand on her left hip. “You writing a book, or what?” LAMF asked. The other boy laughed, sounding like a sour Sal Mineo. Stan asked again, looking straight at the older boy. “East Harlem, where you think?” “Why do you need twenty dollars? The fare’s only ten cents.” “The extra is for in case we get lost.” “It’d be best if you got lost starting now. “ “I mean to get my twenty, and maybe more,” LAMF said, smirking, reaching into his back pocket. Stan took a fast step forward, his right foot coming down on the forefoot of the boy’s sneaker, grabbing his left wrist as it came out of the back pocket a flash of steel, and broke his nose with a short hard jab using his right elbow. He let him fall backward and turned toward the other boy, flipping the switchblade he had taken away from the gangbanger on the ground so its business side was facing front. “Go,” he said to the younger boy. “Go right now before you break out into a sweat and get sick.” The boy hesitated, looked down at the other Seven Saint on the ground, splattered with blood, and ran away like a squid on roller skates. Stan let the switchblade fall to the ground and broke the blade of the knife, stepping on it with his heel and pulling until it cracked at the hinge, and threw it at the older boy who was getting up. It hit him in the chest and bounced away. “The next time I see you,” he sputtered in a rage, on his feet, trying to breathe, his nose floppy, his mouth full of blood. “The next time I see you, you fill your hand with a knife, I’ll break your face again,” Stan said matter-of-factly. He took a step up to the boy, grabbed his ear, holding tight, and spoke softly into it. “Actually, it won’t matter what you do, nosebleed, what you’re doing, who you’re with, where you are. The minute I see you is when I’ll stack you up. Make sure you never see me again. Make sure I never see you.” He took Vicki by the arm, shoved the Seven Saint to the side, and they walked away. “You didn’t have to do that,” Vicki said. “You won plenty of hands at the Flatiron tonight. You might have tossed them a dollar-or-two.” “I know,” said Stan. “But they were working themselves up to be dangerous and that had to stop. The sooner the better.” “They were just kids.” “You saw the scratches on the face of the kid who ran away.” “Of course, the whole side of his face was gruesome.” “The Seven Saints have an initiation to get into the club,” Stan said. “They find a stray cat and tie him to a telephone pole, about head high, and leave the cat’s four feet free. The kid getting initiated has his hands tied behind his back and he gets to become a Seven Saint if he can kill the cat, using his head as a club.” “Oh, my God!” Vicki gasped, stopping dead in her tracks. “How do you even know that?” “I make it my business to know, so I don’t get taken by surprise.” Stan paused, then said, "I don't give a damn about them. I care about you, Dottie, Ezra, and Betty, and what we do. I care about getting it done and getting paid. It’s what I know how to do. I like playing cards, throw in dinner, a dance, a drink with my squeeze, and I’m jake. I don’t need any more.” They passed the USS Maine Monument. Stan pushed a memory of the war in Europe away, even though it had been more than ten years. “I don’t like psycho’s in my face when I’m off the clock,” he grumbled under his breath. He had gotten enough of it in Germany where he had been an Army M. P. It got to be non-stop the year after the war. The whole country was in ruins. Some cities had been reduced to rubble. Expanses of forest were bare. All the trees had been cut down for fuel. The black market was violent like a bazaar run by lunatics. There were let-go prisoners of war and refugees everywhere. Faith healers started popping up on street corners. It was a mess of good and evil. They walked out of the park under a quarter moon, crossing Columbus Circle and strolling down Ninth Avenue. At West 56th Street they turned towards the river, stopping in front of a four-floor walk-up with a twin set of fire escapes bolted to the front of the flat face of the brick building. “Anyway, maybe it will do those greasers some good,” said Stan, fitting his key into the door lock. “Not everybody is as nice as I am. Someday somebody might go ballistic on them.” “Ballistic?” she asked. “Like a rocket, a missile that goes haywire.” “I wish we had a rocket to take us upstairs” she said, as they took the stairs up to the fourth floor. “Oh, darn, we forgot to get pastry.” “Next time,” he said. “The Boricua’s aren’t going anywhere, except here.” At the door of the apartment Stan pushed his key into the lock, opened the door, reached for the light switch, and let Vicki go around him as he did. In the shadow at the back of the front room there was a low menacing growl and a sudden movement. It was Mr. Moto. Mr. Moto was no great sinner, but he wasn’t a saint, either. He thought saints were more honored after their deaths than during their lifetimes. That wasn’t for him. He was alive and kicking and had his own code of right and wrong. If push came to shove and he was ever compelled to get his claws into a Seven Saint, there would be hell to pay for their sins. He crossed the room fast. He lunged at Vicki’s lead leg as she stepped over the threshold. “Hey, watch out for my stockings,” she cried out. Vicki was wearing Dancing Daters. “I’ll smack you right on your pink nose if you make them run.” Mr. Moto skidded to a sudden stop a whisker length from her leg. “That’s better,” Vicki said, bending down to rub his head. The big black cat arched his back and purred. Excerpted from “Storm Drain” at http://www.stanriddman.com. Ed Staskus posts on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. © 2023 Ed Staskus |

StatsAuthorEd StaskusLakewood, OHAboutEd Staskus is a free-lance writer from Sudbury, Ontario. He lives in Lakewood, Ohio. He posts on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybo.. more..Writing

|

Flag Writing

Flag Writing