Looking for TroubleA Story by Ed StaskusLooking for Trouble

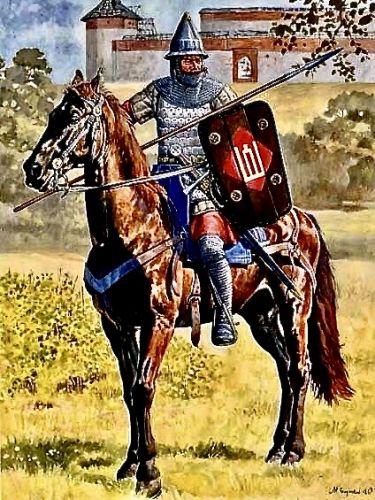

By Ed Staskus Even though Ukraine wasn’t Ukraine in the 14th century lots of folks called it that so that is what it was. The word itself means borderland. The Lithuanians visited every summer. They did it for their health, if not for the health of the natives. When they did they had good times marauding and looting and drinking too much whenever the devil got the better of them. They didn’t control the land so much as take advantage of it. The less governance the better is the way they saw it. “We do not change old traditions and do not introduce new ones,” they said. They were freebooters who became empire builders. The boyars rode fast horses, big and fit, were outfitted in chain mail, wore conical metal helmets, were armed with lances, swords, and knives, and carried a black shield emblazoned with the red emblem of the Columns of Gediminas. They weren’t draftees or recruits. Those who were, walked and died where they stood. The boyars were tough men who could be dangerous in the blink of an eye. The Golden Horde warned would-be enemies of them, “Beware the Lithuanians.” That was all they ever said. They had to be rough and tough. When they went to war they didn’t launch cruise missiles and kill their enemies at great distance, checking the body count with drones. They hacked their enemies to pieces with long swords face to face and watched them bleed to death in the mud at their feet. By the end of the 14th century the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was the biggest country in Europe. Today it is one of the smallest countries in Europe. When they were growing fast and furious they didn’t do it by being soul brothers or good trading partners. They did it by getting on their horses and taking what they wanted. They didn’t bother explaining. The Grand Duchy got started in the early 13th century when Prince Mindaugas united his Baltic forest clans, swamp tribes, and fiefdoms into a feudal state. They were desperate times. The Teutonic Knights were on a rampage. They wanted to incorporate all of Lithuania into the Teutonic Order. They never stopped trying. Between 1305 and 1409 they launched 300-some military campaigns. They slaughtered more peasants than anything else. The Lithuanians beat them back time and again. Finally, in 1410, at the Battle of Grunwald the Lithuanians and Poles destroyed the Teutonic Knights. Most of the order’s leadership was killed or taken prisoner. The Grand Master ran away. They never recovered their former power. When the carnage was over, the Lithuanian-Polish alliance became the dominant political and military force in the region. When I was a kid almost everybody called the Ukrainians Russians. We didn’t call them that because we knew what was up with the Reds. They had done the same thing to Lithuania, enslaving the country, and reaping something anything everything for nothing. Both of my parents came from there after WW2, so we knew what was up. We didn’t have to read between the lines of whatever Washington and Moscow were forever saying. Even though Ukraine didn’t become a nation-state until 1991, after getting their feet wet for a few years after WW1, it was extant in the 14th century, and well before that. We all knew about the Ukrainians when I was growing up, The first Ukes came to Cleveland, Ohio in the 1880s. They settled in the Tremont neighborhood. Their idea was work hard in the factories of the industrial valley, get rich, go back home, buy some land, and live happily ever after. Between the world wars lots of former freedom fighters came. They were goners if they had stayed. Stalin was itching to get his hands on them. Most of them settled in Parma, a southwest suburb, where they built churches, schools, and started their own aid associations and credit unions. We didn’t live in Parma, but on the east side along the lake. Nevertheless, among the Poles, Hungarians, Croatians and Slovenians, and anybody else who could sneak into the country when the Statue of Liberty wasn’t looking, there were some Ukrainian families in our neck of the woods. One of them operated a gas station on St. Clair Ave. not far from where we lived. One of their handful of sons who was our age messed around with us summers, when we had three no-school months to mess around in. His name was Lyaksandra. It sounded like a girl’s name, so we called him Alex. We played pick-up baseball at Gordon Park, from where we could see Lake Erie. We once asked him, taking a break in the action, what he thought about the Russians. He growled, made an obscene gesture, spit sideways, and said, “There are lots of Russki’s in Ukraine. They are liars about everything. They aren’t all bad, but they all hate themselves. We hate them, too.” Ukraine is the second-largest country in Europe. It is bordered by Russia and Belarus, as well as Poland, Hungary, and Romania, among others. It has coastlines along the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov. It has its own language. Most people speak Russian, as well. The Muscovites are always trying to convince them to drop the Uke talk and speak only Russian. “We don’t talk that Russki talk anymore,” Alex said. “Not here, no way.” In the Middle Ages Ukraine, which is about the size of Texas, was the epicenter of East Slavic culture. It was, at least, until the Kievan Rus was destroyed by Mongol invasions in the 13th century. Somebody is always trying to beat up on Ukraine. From then to the 20th century Ukraine was variously ruled by the Lithuanian-Polish Commonwealth, the Ottoman Empire, the Austrian Empire, and the Tsars of Russia. Everybody wanted to be the boss of the Ukes. It’s a miracle they have prevailed and are still prevailing, facing the long odds of going against the vaunted Red Army. The Russians are finding out what it is like to go toe to toe with somebody who is not afraid of them and has the up-to-date American rockets and artillery to back up their bravado. The Ukrainians are fighting an existential battle. Their backs are against the wall. They have nowhere to fall. The Red Army is fighting to save its skin and make it home alive for Defenders of the Fatherland Day. The soldiers throw their uniforms into the nearest sewer when they desert. When I was a boy I played with toy soldiers. There wasn’t any such thing as a Lithuanian mounted boyar toy soldier, so I pretended that anybody on a horse was a Lithuanian knight. They were always the good guys. They won every fight battle and war. They were my heroes. I didn’t know what sons of b*****s they must have been. They weren’t any different than anybody else in power back then. They were all sons of b*****s, including the Holy Roman Church, whose popes ruled by the sword whenever the pen wasn’t convincing enough. In the early 16th century Pope Julius I, the Fearsome Pope, imported Swiss Guards to be his personal bodyguards. He strapped on armor and led the Papal State armies against the Venetians, the French, and the Spanish. His armor plating covered every inch of him just in case the grace of God didn’t get it done, including a helmet made to look like a miter. Everybody on his side was allowed to join the Holy League. Everybody else was badmouthed and excommunicated. After Pope Julius died a rumor had it that if he was denied entrance at the Pearly Gates, there would be hell to pay. He would storm them, St. Peter or no St. Peter, and never mind his set of silver and gold keys. It was every man for himself and God against all. Until the end of the 14th century Lithuanians didn’t give a damn what the Vatican did. They were pagans. They were the last pagans in Europe. The word “Lithuania” is first mentioned in 1009, in an account of the murder of Saint Bruno by “pagans on the border of Lithuania and Rus.” He was trying to convert them. That was a mistake. Their headman, whose name was Dievas, ruled the universe from his kingdom in the sky. He didn’t like anybody popping up with new ideas about Heaven and Hell. Perkunas, the god of thunder and lightning, was his right-hand man and enforcer. The holy fires were guarded by Vaidilutès, the Lithuanian equivalent of Vestal Virgins. They buried their dead with food and household goods. The last pagan grand duke was buried with his hounds, horses, and falcons. When they finally joined the God-fearing club it was a political move. They were doing a dynastic union with Poland, and one of the conditions the Poles laid down was that the Lithuanians had to convert to church-going and dump their veneration of the forces of nature. It didn’t change their business plan in Ukraine, other than to make them more organized. They transitioned from frat parties to fancy dress balls. The Grand Duchy of Lithuania had controlled Belarus for some time and when they went after Ukraine they got it, extending their control to the open steppe and eventually to the Black Sea. The Ukes learned to “Beware the Lithuanians.” When they started to get what they wanted they left their freebooting days behind and started building castles to keep their loot secure. It was a ten-day ride from Vilnius to Kiev. Why not ditch the seasonal exploitation and make the most of the four seasons? It wasn’t their land, but it is finders keepers. They meant to keep what they had subjugated. The Ukrainians didn’t have a say in the matter. They told the Ukes, “We may not be perfect but we’re Lithuanians so it’s almost the same.” The Ukes said, “We promise not to laugh when your oven is on fire.” The Lithuanians weren’t offended. They just said, “Show us the goats.” They built the Lutsk Castle, which later became a museum. They built the Olyka Palace, which later became an insane asylum. They built the Kremenets Castle, which later fell into ruins after the Cossacks sacked the city at the bottom of the hill. In the meantime, the boyars lived the high life. They started with red borscht, green borscht, and cold borscht. They feasted on holubtsi, cabbage leaves stuffed with minced meat, rice, and stewed in tomato sauce. They ate slabs of kholodets, a cold jellied meat broth. They drank vodka between courses. Ukrainians to this day drink more vodka than beer. When they were done with dinner they went to bed, snoring and cabbage farting in their sleep. Even though the Lithuanians always said the Ukrainians welcomed them with open arms, they built their castle-fortresses on high hills with steep inclines, the rockier the better, fitted with one main gate and plenty of towers, arrow slits, battlements, and dungeons. They kept big rocks and hot oil handy to toss down on door-to-door salesmen. If you ended up in the dungeon you found out soon enough they weren’t playing Dungeons and Dragons. Imperialism is never cozy and consensual. It’s more like assault and battery. The movers and shakers of power politics don’t get thrown in jail until long after they are dead. My friend Alex had never heard of Lithuanians living it up in Ukraine. He was surprised to hear they had once been a super power. He was chagrined to find out there were more invaders of his homeland than he had realized. “How come the Lithuanians push us around back then?” he asked. Most of us playing ball at Gordon Park were second generation Lithuanian Americans. We weren’t even teenagers, yet. None of us had a good answer, much less a sensible answer of any kind. “Somebody always wants to be the top dog,” Kesty said. “No, that wasn’t it,” Arunas said. “They just wanted to have somebody else do all the work, like make dinner and clean the toilets.” “It was the Ukrainian girls,” Romas said. “Ukrainian girls are hot.” Romas was over-sexed, and everybody knew it. Nobody had any other ideas. We went back to playing ball in the summer sun. When we got overheated we walked to the shore and sat on the edge of a cliff in the breeze. Lake Erie was in front of us, the water rippling, the tips of the waves white. “Can we see Ukraine from here?” Alex asked. “No, it’s that way,” Arunas said pointing over his right shoulder. When we looked all we could see was Bratenahl, where rich people lived in mansions. They made the rules, for what they were worth. Our grade school class practiced duck and cover once a month, just in case the Russki’s dropped an atomic bomb on Cleveland. We brought our own lunches every day but wondered where our next lunch was going to come from if all the food stores got blown up. Many of the Bratenahl bluebloods had their own fallout shelters. They didn’t worry overmuch about starving. All good things must come to an end. The Lithuanians were strong in Ukraine for several centuries, but the deal they made with Poland reaped a better harvest for their next-door neighbors than my ancestors. The Poles say, “A good appetite needs no sauce.” By the mid-16th century Lithuanians were sauce. Their goose was cooked. The dynastic link was changed to a constitutional one by the Union of Lublin in 1569. Ukraine was set free of the Lithuanians but was annexed by Poland the next day. The more things change the more they stay the same, until they don’t. The new would-be colonialists calling the shots in the Kremlin are finding that out, to their discomfiture. They make a wasteland and call it New Russia. They have been looking grim lately. The once-mighty boyars are rolling over in their graves, their visions of conquest and glory gone sour, their iron fists gone rusty. Lithuania has gone egalitarian, joined NATO, and gotten out of the plunder and pillage business. Ed Staskus posts on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. © 2023 Ed Staskus |

StatsAuthorEd StaskusLakewood, OHAboutEd Staskus is a free-lance writer from Sudbury, Ontario. He lives in Lakewood, Ohio. He posts on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybo.. more..Writing

|

Flag Writing

Flag Writing