Bomb City USAA Story by Ed StaskusBomb City USA

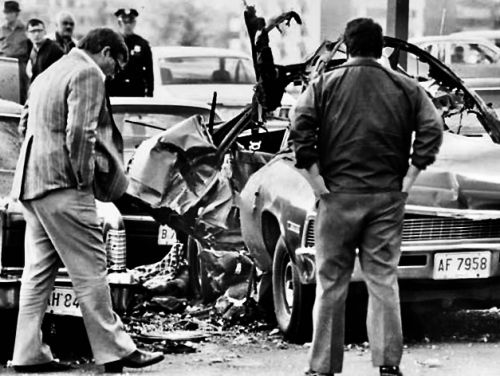

By Ed Staskus When I went to work as the night clerk at the Versailles Motor Inn on East 29th St. and Euclid Ave. in the mid-70s, Cleveland, Ohio was the bomb capital of the country. There were 37 bombings in the surrounding county in 1976, one every ten days, including 21 in the city, making it tops in the United States, according to the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, and Firearms. They called it “Bomb City USA.” “A bombing sends a real message. It commands a lot of attention,” said Rick Porello, a northeast Ohio career police officer. “Danny Greene was said to have paid Art Sneperger, his main explosives guy, extra if the bombing generated news coverage. Art got paid a bonus if the thing got on television or in the newspapers.” If it bleeds it leads was the motto of newsmen everywhere. The explosives guy made his own headlines in 1971 when, at the behest of gangster Danny Greene, he suddenly found himself in hellfire while planting explosives under the car of the Irishman’s old friend and new enemy Mike Frato. Fumble fingers don’t pay, although the word on the street was that Danny Greene had set the bomb off from across the street. He had come to believe Art had ratted him out to the FBI. Six years later Danny Greene was blown up walking out of a dental office in Lyndhurst. The gangster paid cash, so the dentist ignored the sonic boom. The tooth fairy cancelled her scheduled visit that night. Money was no good where the Irishman was going. Nobody knew anybody who shed a tear. The plus-sized bomb was in a small Chevy Nova parked next to his Lincoln Continental. It was a Trojan Horse. When it went off, set off by remote control, the Nova, Continental, and Irishman were reduced to corn flakes. The gangster usually wore all green clothes, wrote in green ink, and drove a green car. He wasn’t going incognito. It was easy to see it was him getting into the Lincoln. The bomb blew one of his arms one hundred feet across the parking lot. Crows came running. The lucky Celtic Cross he wore around his neck was driven into the asphalt. The coroner didn’t bother trying to put him back together. The Nova came from Fairchild Chevrolet in Lakewood. “We heard the owner of the car lot might have been involved,” said Bob Gheen, a teenager at the time. The Chevy had once been his father’s car. “They never transferred the title out of my dad’s name. Rick Porello from the Lyndhurst Police Department showed up at our door on Saturday morning and drove us to identify what was left of the car. We had to answer several questions and that’s pretty much the last we heard of it.” I was taking classes at Cleveland State University but because I didn’t have a scholarship or any grants, and nobody would give me a loan, I had to pay tuition fees and book costs myself. I was living in Asia Town, in a Polish double on East 34th St, upstairs in a two-bedroom with a roommate, but even though I knew how to live on next to nothing, I needed a little to pay the bills and some more to pay for school. The Versailles Motor Inn was built in the mid-60s, meant to piggyback on the Sahara Motor Inn a few blocks away at East 32nd St., which was built a few years earlier. The Sahara wasn’t hiring, but the Versailles was, and I thought if it is anything like the Sahara, I am the young man for the job. I later found out I was the only young man to apply for the job. All the rooms at the four-story Sahara featured a television, air conditioning, piped-in music, and a dial phone, the first ones in rooms in northeast Ohio. There were three presidential suites and three bridal suites. There was a heated swimming pool, a dance floor, and a patio on the second floor. There was a continental dining room with velvet armchairs and a starlight ceiling. There were four cocktail lounges. The waitresses wore Egyptian outfits, and the waiters wore fezzes. There were eight-foot paintings of Cleopatra, King Tut, and Queen Nefertiti in the lobby. Other than the Versailles had 150 rooms, exactly the same as the Sahara, that is where the resemblance ended. The Versailles had a bar restaurant, a coffee shop, and a lobby. It featured sunken pit seating in the lobby where nobody ever went. The lighting was bad. The front doors facing Euclid Ave. were kept locked under penalty of death. Unlike the Sahara where the plants in the lobby were real geraniums, rhododendrons, and palm trees, everything at the Versailles was fake. The front desk was cheap veneer and the carpet was cheap, too, going threadbare. There was a drive-up entrance on the side of the building at one end of the front desk and the door to the bar restaurant at the other end of the desk. There were two elevators that made a racket going up and down. The Sahara attracted weddings, conventions, and business meetings. TV crews filming episodes for “Route 66” stayed there sometimes. The Versailles attracted business like peddlers, couples on a tight budget, short-term construction workers, dodgers who left small tips and said hold all their calls, and the John and Jane trade. I was glad to get the job since I could walk there from where I lived in Asia Town, it paid reasonably well, and I would have about half of my hours from 11 PM to 7 AM to do homework. I reconciled the day’s receipts before and after my shift. We had a floor safe bolted down in the back office. My responsibilities were mainly checking in guests and taking reservations. I gave directions to late-night callers, answered inquiries about our hotel services, which was easy enough since there were hardly any, and made recommendations to guests about nighttime dining and entertainment options, which was also easy. “In the 1970s, downtown was dead,” said John Gorman, disc jockey and program director at radio station WMMS. “The Warehouse District and Playhouse Square weren’t happening yet. There was no reason to come.” The nickname of the progressive rock station was ‘The Buzzard.’ Downtown Cleveland’s nickname was ‘The Wasteland.’ One night, while nothing much was happening on my side of downtown, and I was in the back office boning up for an exam the next week, Shondor Birns, Public Enemy No. 1 in Cleveland for a long time, strolled out of Christy’s Lounge, a strip club on Detroit Ave. on the near west side. It was across the street from St. Malachi Catholic Church. It was Holy Saturday, easing into Easter Sunday. There wasn’t going to be any resurrection for the gangster after what was going to come off happened. During Prohibition the Birns family turned to bootlegging, working a still in their basement for Cleveland Mafia boss Joe Lonardo. Mother Birns went up in smoke when the still exploded. After Shondor dropped out of high school, he was subsequently arrested 18 times in 12 years. After his 6th or 7th arrest a Cleveland prosecutor declared, “It is time the court put away this man whose reputation is one of rampant criminality.” He hooked up with the Maxie Diamond gang and got into the protection rackets. He muscled into the numbers and policy games. He opened restaurants like the Ten-Eleven and Alhambra. His big mistake was hiring Danny Greene as an enforcer. The relationship soon soured and Birns put a contract out on Greene. When the Irishman found a bomb in his car, he disarmed it himself and showed it to Cleveland Police Lieutenant Ed Kovacic, who offered him police protection. “No, for whatever it’s worth,” Danny Greene said, leaving the Central Station and taking the bomb with him. “I’m going to send this back to the old b*****d that sent it to me.” When the old b*****d left the girlie show, got comfortable behind the wheel of his car, and turned the key in the ignition, a hefty package of C-4 exploded beneath him. His head was blown through the roof of his Lincoln Mark IV. The cigarette he had been meaning to light was still between his lips. His torso landed somewhere outside the passenger door. His legs landed somewhere farther away. Mary Nags owned a print shop on Detroit Rd. It shared a common parking lot with the strip club. She got a call from the cops telling her not to come to work on Monday. “They said a man had been blown up and parts of him were scattered around in our back lot.” The forensics men spent a day finding all the bits and pieces of the once intact Shondor Birns. Police detectives focused on the numbers big men in the ghetto with whom the gangster had been feuding. That turned out to be a dead end. “It’s dumb to talk about blacks doing Shondor,”one of the big men said. “He wasn’t no bad fella. He was white but it didn’t make no difference. Shon had a black soul. He was black through and through.” Everybody knew Danny Greene had ordered it done, but charges were never brought after the actual bomber died. The Irish mobster had contracted Hells Angel Enis “Eagle” Crnic to do the job. The biker was later blown to bits while placing explosives to the underside of a car belonging to “Johnny Del” Delzoppo. If the district attorney wanted to pursue the case, he would have to deliver his subpoena to the bottomless pit, where the Eagle was living next door to Art Sneperger. The first time I was robbed at the Versailles Motor Inn I wasn’t robbed, because I was surprised and reacted without thinking. A young black man filled out a registration card, handed me a twenty, and when I turned around to get him his key, started rifling the cash drawer. “Hey!” I shouted, lunging forward and smashing the drawer shut on his hand. He ran out yelping and cursing. The second time I was robbed I was robbed. The young black man didn’t bother registering. The bandit was wearing a jacket and suggested he had a gun in his jacket pocket by pointing the pocket at me. “Know what I mean?” he said. I had seen plenty of cops and robbers movies. I knew what he meant. “It’s not my money,” I said opening the drawer, stepping back, and raising my hands to the ceiling. What’s a simple man to do? He said I could put them down, but “don’t mess around.” He took all of the night’s take except the loose change. I called the police, a patrol car pulled up, I made out a report, and they left. The men in blue seemed largely indifferent. “Don’t let it happen again,” my boss said in the morning. He wasn’t indifferent about the missing money. “What do you suggest?” “Do you want to keep your job?” “I guess so,” I said hedging my bets. “All right then,” he said, and that was the end of his word to the wise. My last night at the Versailles Motor Inn was the same as most nights, until it wasn’t. I was busy until 2:30, then it was slow as a shuttered orphanage. I sat in the back office reading until I got drowsy. I took a walk through the gloomy lobby to wake myself up and was standing behind the front desk doing nothing when the next split second there was a roaring bang and bright flash. The doors of the bar restaurant flew off their hinges and every single bit of glass the length of the hallway was blown to smithereens. Other than the echo from the blast I couldn’t hear anything, slowly backing away from the desk and backing out the side door, sidling along the outside wall until I came to the front of the building. I stood outside until I was breathing again, and my hearing started to come back. I decided I wasn’t hurt since nothing hurt. Back inside the dust was settling and it didn’t look like too much was on fire. The phone was still working. I called the police and they arrived in the matter of a minute, the fire department hard on their heels. The firemen hauled hoses inside and sprayed water on everything from one end of the bar restaurant to the other. The hardwood bar was split in half. All the tables and chairs were helter-skelter. Many of them were splintered. All of the bottles and glasses and mirrors were shattered. It was a soggy mess when the firemen got done with it. There were 40 or 50 guests tucked into their beds when the bomb went off. Some of them on the lower floors were woken up by the ka-boom. A policeman stood by the elevator and whenever somebody came down asking what the noise had been told them to go back to bed. I went over what happened with a detective, twice. He asked me a hundred questions but finally told me to go home. It was five in the morning. I walked up East 30th St. to Payne Ave, past Dave’s Grocery and Stan’s Deli, to my rented second floor on East 34th St. I didn’t see another soul, although a couple of cars went by. My roommate was dead asleep. Mr. Moto my Siamese cat followed me into my bedroom and jumped on top of me when I fell into it. He curled up while I lay awake. I quit by phone the next day. The only time I went back was to collect my last paycheck. The big cheese looked at me sideways like I had something to do with the bombing. When I asked, he said the police had found a door forced at the back of the coffee shop, and believed that’s how the intruder got in, taping three sticks of dynamite to the underside of the bar. He said I was lucky the wood was oak. “One stick can blow a 12-inch-thick tree right out of the ground, do you know?” he said. “I don’t know and I don’t care,” I said. There were sheets of plywood hammered up everywhere. A month later I heard talk that the bar restaurant proprietor, who leased it from the Versailles, had fallen behind paying his protection money and the bombing was a way of settling accounts. The Mob was big in Cleveland in the 1970s. When John Scalish died after 30-odd years as the power broker in town, Jack “King of the Hill” Licavoli took over. He lived in an unassuming house in Little Italy, up the hill towards Cleveland Heights. “Jack was the last of the old-school Cleveland mobsters,” said James Willis, his downtown lawyer. “Cleveland had the best burglars, thieves, and safe crackers in the country. I know, I represented a lot of them.” Jack White, another of his names, a play on his dark Sicilian complexion, got his start bootlegging in St. Louis. He came to Cleveland in 1938 and worked his way up. “A lot of the guys coming up were just out for themselves, not Jack. He looked out for the operation and he was so good at his job that I thought it would never end,” his enterprising lawyer said. “He was very secretive and not at all flamboyant. We would only ever talk in person.” “No one thought it would be Licavoli taking over,” Rick Porello said. “He was an old miser. One time he was caught by store security for switching the price tag on a pair of trousers. When they found out who he was they dropped the charges.” I soon found work in the Communications Department at Cleveland State University, on the 16th floor of Rhodes Tower, working for their new film studies professor. I was an English major, but movies were close enough. They were becoming the new literature. My job was picking up whatever art house film my boss was showcasing from the mail room, roll the 16 mm projector out of storage, screen the movie to his class, and send it on to the next place that wanted it. In return I got free tuition and a closet that passed for an office. I watched many French New Wave movies, Japanese samurai movies, and 1940s Warner Brothers crime movies during my work-study year, films that the CSU library had tucked away in secret places. I projected them on my office wall at the end of the day. I didn’t have a TV at home, but the movies I watched were better than anything on TV, anyway. Two years after I left the Versailles Motor Inn, John Nardi, who was secretary-treasurer of Vending Machine Service Employees Local 410 and high up in the mob’s chain of command, sauntered out of his office a couple of blocks away from where I had watched countless film noirs, stepped into his Oldsmobile 98, turned the key, and was blown to kingdom come. The device under his seat was packed with nuts and bolts. Bomb City USA was alive and well. Ed Staskus posts on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. © 2023 Ed Staskus |

StatsAuthorEd StaskusLakewood, OHAboutEd Staskus is a free-lance writer from Sudbury, Ontario. He lives in Lakewood, Ohio. He posts on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybo.. more..Writing

|

|

|

Flag Writing

Flag Writing