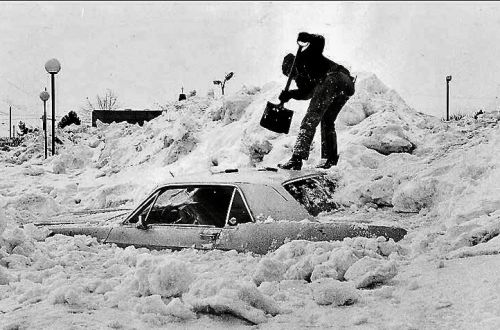

Snow GlobeA Story by Ed StaskusSnow Globe By Ed Staskus When I was a kid growing up in Sudbury, Ontario it started snowing the last day of summer, snowed through Halloween Thanksgiving Christmas, and got down to business on New Year’s Eve. The next day barreling into the new year it snowed some more. It kept up its business until mid-April with a fire sale now and then in the month of May. All told between 100 and 140 inches of snow fell every winter during my childhood. My father built an igloo in the back yard so that when we were snowballing, we would have someplace to shelter if a blizzard roared down from the Northwest Territories. My brother sister and I sat inside on crates looking out of windowless windows as heavy clouds lowered the boom on us. When Canadian Pacific trains hauling nickel rumbling past on top of the cliff face behind our house on Stanley Street wailed, we wailed right back. Snow cover in Sudbury starts to get deep in December and remains deep through most of January to mid-March. By the end of April, the snow is usually gone. The city is free of snow every year in July and August. Extreme cold and winter storms kill more Canadians than floods, lightning, tornadoes, thunderstorms, and hurricanes combined. A year before I was born the Great Appalachian Storm struck. It was Thanksgiving weekend. It dumped nearly a foot of snow on my hometown every day for a couple of days. A blustery wind made sure everybody got their fair share. Ramsey Lake froze solid. My father-to-be went skating. He wasn’t able to get to the INCO mine where he worked as a blaster, but he was able to get to the lake with his ice skates. When the snowfall was finally cleared away, it was December. After we moved to Cleveland, I sent a postcard to my friends back on Stanley Street saying Americans were snowflakes when it came to snow. “They complain about a couple of inches. Most days there isn’t nearly enough of it to make a decent snow angel.” It wasn’t exactly true, but it was true enough. In general, snowfall in northern Ohio is about 50 inches a year. Twenty years later I had to eat my words. The Blizzard of 1978 started in Indiana near the end of January. The Hoosiers might have kept it to themselves, but they didn’t. The day after the storm buried their state it buried Ohio. More than a foot of snow fell in one day, on top of a foot-and-a-half that was already on the ground. The wind huffed and puffed. Snowdrifts buried cars trucks homes businesses. The wind chill made it feel like 60 below zero. East Ohio Gas pumped record amounts of natural gas to needy furnaces. My parents were living in Sagamore Hills. When the weather cleared, they called me about the snow on the roof of their ranch-style house. My father was afraid the snow load would damage the roof, maybe even make it cave in. I thought he was exaggerating, until my brother and I climbed a ladder to see for ourselves. The roofline was long and low-pitched. We found ourselves thigh-deep in heavy snow. We spent the rest of the day slowly shoveling and pushing it over the side of the eaves. “My dad made me shovel a path out the back door for our dachshund so he wouldn’t do his business in the house,” Joe Bennett said. “I got about two feet out and called it a day.” The storm was characterized by an unusual merger of two weather systems. Warm moist air slammed into bitter ice-cold air. “The result was a very strong area of low pressure that reached its lowest pressure over Cleveland,” the National Weather Service reported. That day’s barometric pressure reading of 28.28 inches is the lowest pressure ever recorded in Ohio and one of the lowest readings in American history. By the end of the month, a few days later, Cleveland recorded 43 inches of snowfall for the month, which is still a record. It was called “The Storm of the Century” or simply “The Superbomb.” The wind averaged nearly 70 MPH the day it started. Gusts hit 120 MPH-and-more on Lake Erie. Ore boats coming from Lake Superior hunkered down, and crewmen stayed close to oil heaters. “I was a deckhand on a lake freighter,” said August Zeizing. “We were stuck in ice about 9 miles off Pelee Point when the storm hit. We had steady 111 MPH winds gusting up to 127 MPH for about six hours. Our orders were to stay below decks and keep our movements to a minimum.” More than 50 people died, trapped in wayward cars and unheated houses. A woman froze to death walking her dog. There was more than $100 million in property damage, what many said was a conservative estimate. The governor called up more than 5,000 National Guardsmen, who struggled to reach the cities they were assigned to. The Guardsmen used bulldozers and tanks outfitted with plows to clear roads streets highways and rescue the stranded. “My dad and I drove down I-71, which was closed, to get to our farm in Loudonville,” said Paula Boehm. “We had chains on all four tires of our Buick station wagon.” The only other traffic was National Guard M113 personnel carriers. “We made it.” Car owners stuck homemade signs saying “Car Here” on top of mounds of snow. It alerted snowplow drivers to what was under the pile of white. Motorists abandoned their cars and pick-ups helter-skelter. It was a three-dog Siberian day night and the next day. In some places it went on and on, often in the dark, as power wires were blown loose or broke off poles from the weight of ice. I was in Akron the morning the storm struck. I had no idea a blizzard was on the way. The forecast the night before didn’t sound awful. “Rain tonight, possibly mixed with snow at times. Windy and cold Thursday with snow flurries.” I was visiting a friend, had stayed overnight, and was driving my sister’s 1970 Ford Maverick. I needed to get the car back to her that day. National Weather Service Meteorologist Bob Alto got to work at six in the morning Thursday at the Akron-Canton Airport. He was able to go home late Sunday night. “Nobody could get in and nobody could get out,” he said. “The roads were all closed. There were three of us and we had to ride it out there at the airport.” Cessna and Beechcraft two-seaters were flipped over like paper airplanes. Meteorologists didn’t call the storm a “Superbomb.” They called it a “Bombogenesis.” It was their term for an area of low pressure that “bombs out.” I got up early and got going. When I did the temperature started falling fast. By the time I got coffee and an egg sandwich and got on I-77 to go home the temperature had fallen from the mid-30s to the mid-teens. It was a fast cold snap. The rain turned to ice and snow, snowing like there was no tomorrow. I couldn’t see any lane markers and could barely see the road. The Maverick was a rear wheel-drive with no traction to speak of. I kept it at a steady 25 MPH unless I slowed down, which I did plenty of. Jack-knifed tractor trailers littered the shoulders. One truck and its trailer were upside down. There were spun-out in the lurch cars everywhere. When I passed the Ohio Turnpike, I saw it was closed, the first time that had ever happened in the history of the turnpike. I found out later that I-77 was the only highway that didn’t close. Marge Barner’s husband-to-be drove a yellow bus full of kids to school as the blizzard started. He dropped them off. Not long afterwards he got a call saying the school was closing. He went back and that afternoon started plowing parking lots. “He was out for 13 hours in an open tractor and ran out of gas several times. He didn’t have a radio to call for help,” Marge said. He had to help himself, walking with a can to gas stations. “He lost feeling in his arms when he got home, which finally came back as he warmed up. His ears were frostbitten.” I kept on slow poking north. I had plenty of gas, having filled up the tank the night before after noticing I was driving on fumes. The car radio was no help, broadcasting the same bad news over and over. The car heater wheezed and groaned but stayed alive. Driving in the swirling snow hour after hour straining to see and stay on the road was nerve-wracking. I kept my gloves on and my eyes glued to the road. “I was 7 years-old and we lived in a drafty, old farmhouse in Fremont,” said Susan Beech. “The power went out, so the furnace went out, but our oven ran on propane, so it still worked. My dad set up cots and sleeping bags in our kitchen, and stapled blankets over the doorways. We ran the stove around the clock, leaving the oven open so the heat filled the room. It was like winter camping in the kitchen.” After I passed another overturned truck I thought, if that happens dead center on the road somewhere in front of me, I am a goner. I am going to end up in a miles long traffic jam. ODOT’s plows won’t be able to get around the mess. Wreckers won’t be able to get to the wreck to move it out of the way. We will all be at a standstill and run out of gas and either freeze or starve to death. I saved half my egg sandwich for later. I checked my gas gauge and was relieved to see I still had more than half a tank. “I was a teenager living four miles from the nearest town during the 1978 Blizzard,” said John Knueve. “We lost power the first night and had to rely on a small generator, which could power just one appliance at a time.” They fed the generator drops of gasoline at a time. “A two-lane state highway ran in front of our house, but even when they finally managed to clear it, an 18-wheeler would pass by, and we’d never see it for the thirteen fourteen-foot drifts which encircled the entire house. We were trapped for most of a week before my brother-in-law made it down with his tractor to break through.” In some parts of the state massive snowdrifts as high as 25 feet buried dog houses sheds garages and two-story homes. I got close to Cleveland before nightfall. I-90 looked closed, so I took St. Clair Ave. to Lakeshore Blvd. to North Collinwood. I lived two blocks from Lake Erie. When I pulled into my driveway the Maverick got stuck immediately. I didn’t try digging it out. My sister would have to wait for her car. Spring was only a few months away, anyway. It was even windier and colder in our neighborhood on the lakeshore than the rest of the world. The furnace was trying hard, but the house stayed cold no matter how hard it tried. I wrapped myself up in a comforter. The windows rattled and the house shook whenever a hurricane-like blast of wind hit it. “Oh, that was awful,” Mary Jo Anderson said about the howl of the wind. “Nobody slept much that night. We had never heard that kind of noise. You know, how your house shakes and squeals.” Her husband, Rich, set off in his Ford Pinto for work that morning. The Pinto wasn’t the ugliest and most unsafe car ever made, but it was a close call. The seats made for sore asses after an hour-or-so and God forbid getting rear-ended. The gas tank had a design flaw that made it prone to exploding on impact. Two years earlier news had broken that Ford’s company policy was that it was cheaper to pay the lawsuits of the car’s fire victims rather than re-design the problem. After that news flash there was hell to pay. Rich was about a mile up the road in his Pinto when he was brought to a standstill. He couldn’t drive any farther because the wind was ferocious. The car was a lightweight, barely breaking two thousand pounds. “The ice was on the window of his car, and he was trying to reach his arm out and scrape the ice off,” Mary said. “He opened the car door, and the wind almost ripped it off. The car spun around in a circle. The door wouldn’t close. It was broken. He had to hold it shut while he drove home with the other hand. He was happy to make it back.” That night I watched the WEWS Channel 5 news show. There wasn’t a lot of footage of the storm even though a film crew had gone searching for news on downtown streets. “It was impossible to see. Wind howling. Bitter, bitter cold,” Don Webster the weatherman said. “They couldn’t shoot anything because of the cold and wind. I couldn’t even talk because I got so cold. I couldn’t say anything.” When I changed the station to WJW Chanel 8, Dick Goddard called it a “white hurricane.” Susan Downing-Nevling drove a Chevy Chevette to work. It was a basic reliable car. Her boss was mad because she hadn’t made it in to work on Thursday, even though she told him people couldn’t get to their cars because the wind was knocking them down as they tried to walk to their vehicles. “So, on Friday I got up, dug my Chevette out, and drove to work on W. 44th St. and Lorain from Middleburg Hts. I didn’t stop once but it still took me four hours. When I got to work, it was closed. My boss was stuck at home. A couple of others who made it like me and I went to the Ohio City Tavern for the afternoon.” They cheered the bartender who had walked over from up the street. When the storm moved on that weekend it moved northeast, hooked up with a nor’easter, and walloped New England, as well as New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania. Instead of “Superbomb” it was called “Storm Larry” up and down the east coast. Philadelphia got 16 inches of snow, Atlantic City got 20 inches, and Boston was buried by 27 inches. The ice snow wind killed almost 100 people and injured about 4,500. It caused more than $500 million in damage. Once it was all over local stores started selling t-shirts that read, “I Survived the ’78 Blizzard!” I didn’t buy one. What would have been the point? It wasn’t going to keep me warm and dry if the blizzard came back. I bought a puff coat. I was hedging my bets. The Blizzard of 1978 might have been “The Storm of the Century,” but there were 22 more years left in the century. I wasn’t expecting to see it’s like anytime soon, but you never can tell. If you want to see the sunshine you have to weather the storm. Ed Staskus posts on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. © 2023 Ed Staskus |

StatsAuthorEd StaskusLakewood, OHAboutEd Staskus is a free-lance writer from Sudbury, Ontario. He lives in Lakewood, Ohio. He posts on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybo.. more..Writing

|

Flag Writing

Flag Writing