10 Cent Beer NightA Story by Ed Staskus10 Cent Beer Night

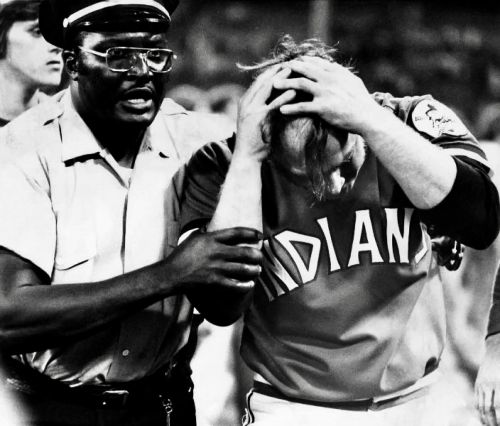

By Ed Staskus When my friends and I heard there was going to be a 10 Cent Beer Night at Municipal Stadium, we started saving our loose change. It was Saturday morning June 1, 1974. Beer Night was going to be on Tuesday night June 4th. We didn’t have much time, but we had plenty of motivation. When the big night arrived, our pockets were full of nickels, dimes, and quarters. We met at East 30th St. and St. Clair Ave. and took a bus to East 9thSt. From there we walked to the ballpark. Municipal Stadium opened in 1931 and was the home of both the Cleveland Indians and Cleveland Browns. Two days after it was formally dedicated Max Schmeling fought Young Stribling for the World Heavyweight Championship. The two sluggers brawled for the full 15 rounds. In the end Young Stribling was covered in more bumps, bruises, and blood than Max Schmeling, so the German won the match on a TKO. A month later the Tribe played their first game there, losing to Lefty Grove and the Philadelphia Athletics one to nothing. The crowd of more than 80,000 set a major league record. When it was built, and for many years afterwards, Municipal Stadium was the biggest baseball stadium in the country, although by the 1970s it was drawing the smallest crowds in the country. A month earlier only 4,000-some fans showed up to watch the Indians beat the Boston Red Sox. There were two reasons everybody stayed home and watched something else on TV. The stadium was built all wrong, for one thing. It was cavernous. Relief pitchers had to be driven to the mound from the bullpen. Even when new outfield fences were installed shrinking the size of the playing field, it was still 470 feet from home plate to the bleachers in straightaway center field. High and deep fly balls went there to die. We always sat in the cut-rate seats. No wannabe home run ever reached us. The upper deck was even farther from the field. Nobody wanted to sit in the stratosphere with high-powered binoculars. By the late 1960s the place was falling apart. It looked like Miss Havisham’s mansion. It stood on the south shore of Lake Erie, a wheezy open-air mausoleum. It was a dismal hulk, especially in the spring and fall when cold winds blew in off the lake. During the summer, during night games, the lights attracted swarms of midges and mayflies. The bathrooms were unbearable for many reasons. Only the desperate ever visited them, however briefly. On top of everything else, the Tribe couldn’t punch its way out of a paper bag. In the 1950s they were routinely winning 90, 100, and even 110 games every season. They won championships. By the 1960s they were lucky to win 80 games a season. In 1971 they lost 102 games and won only 60, finishing so far out of first place fans lit candles. The locker room got sad and gloomy. The Tribe lost more games during the decade of the 1970s than during any other decade of the team’s long life. When we got inside the stadium we were surprised by how many fans were there, about 25,000 of them, although we shouldn’t have been. Besides the cheap beer, payback time was in play. A week earlier in Texas, the Indians and the Rangers had gotten into it. In the bottom of the eighth inning a Tribe pitcher threw behind a Ranger batter’s head. A few pitches later the batter laid down a bunt. The pitcher fielded the ball and tagged the runner out. The runner didn’t stop running, clubbing the pitcher in the face with a forearm as he ran past. When he got to first base he headbutted the Tribe’s first baseman in the nuts. The first baseman started swinging. Both benches emptied. After the fracas, as Indians players and coaches returned to their dugout, they were greeted with stale pretzels and warm beer hurled by Texas Ranger fans. Dave Duncan, the short-tempered Cleveland catcher, had to be restrained from storming the stands. After the game a reporter asked Rangers manager Billy Martin, “Are you going to take your armor to Cleveland?” Billy Martin replied, “Naw, they won’t have enough fans there to worry about.” The following week sports radio talk show hosts whipped up the ire of Cleveland’s baseball fans. It was billed as “Revenge Rematch Time.” The Cleveland Plain Dealer printed a cartoon of Chief Wahoo wearing boxing gloves. The caption read, “Be Ready for Anything!” 10 Cent Beer Night was the dreamchild of the Tribe’s sales and marketing department. “We were on a mission to save baseball in Cleveland,” said Carl Fazio, one of the men overseeing promotions. “We did everything possible to make baseball successful in our town. If we were going to fail, it wasn’t going to be because we didn’t try things.” Tuesday was a hot sticky night. The sky was clear and the moon was full. Twice as many fans showed up as the sales and marketing showmen expected. “It was a stinkin’ humid night, and you kind of had a feeling things weren’t going to be good,” said Paul Tepley, a Cleveland Press photographer. “Billy Martin stood in front of the Rangers dugout before the game heckling the fans, and the fans were heckling him. It had the makings of a bad night.” No sooner did anybody step into the stadium than they made a beeline to the special tables manned by teenagers and barely adults selling the low-cost beer. The legal drinking age in 1974 was 18. Banners behind the tables said, “From One Beer Lover to Another.” The regular price was 65 cents. The promotional price of 10 cents was a big discount. There was a limit of six cups per purchase but no limit on how many purchases anybody could make during the game. The first Beer Night had been staged three years earlier. It had been Nickel Beer Day. There were some incidents then but they mostly involved horseplay and vomit. Some fans brought pockets full of firecrackers and smoke bombs to 10 Cent Beer Night. They blew them off in the stands and threw some on the field before the game started. When the first pitch was thrown for a strike everybody settled back with their suds and tuned into the action. In the second inning a woman sporting a bouffant ran to the on-deck circle, lifted her shirt, and flashed the crowd. She was beaming smiles. She tried to kiss home plate umpire Nestor Chylack. He was not in a smooching mood. Everybody cheered the sight of b***s but gave the umpire a Bronx cheer for ducking the kiss. The Rangers took a three to nothing lead when Tom Grieve slammed a home run with men on base. As he went around second base a well-built naked man slid into the bag behind him. He was wearing two black socks. We thought he might be a businessman. When the streaker got up he saluted the crowd before dashing away. His butt was road rash red. He ran through center field towards the bleachers. One of his socks got loose. By the time he got to the fence in front of us, he was down to the other sock. He vaulted over the fence and disappeared under our seats. The next inning a father and son ran out onto the field and simultaneously mooned the crowd. The son’s butt was white. The father’s butt was cream cheese white. When the special tables selling 10 cent beer started to run dry the Stroh’s Brewing Co. sent a tanker full of brew to the back of the ballpark. Fans gathered at the industrial spigots fastened to the rear of the truck. Before the truck arrived every Rangers player who stepped up to the plate had been roundly booed. Twenty minutes after the truck got there, the crowd was throwing things at them. “I bet I had five or ten pounds of hot dogs thrown at me,” said Mike Hargrove, a Rangers rookie playing the infield. “A gallon jug of Thunderbird landed about ten feet behind me.” When he realized what he had done, the man who threw the half-full jug of fortified wine demanded it back. Fans threw rocks, batteries, and golf balls. One man threw a tennis ball and was almost laughed out of the ballpark. The bullpens had to be evacuated after cherry bombs were lobbed into them. Everything went to hell in the home half of the ninth inning. Everybody with kids and a wife had already fled. The Tribe put together four straight hits and a sacrifice fly. They tied the game at 5 runs apiece. The winning run was standing on second base. Unfortunately for the Indians, that was as far as he ever got. Before he could make a move two young men ran out on the field towards Rangers outfielder Jeff Burroughs. They were greased for trouble. One of them tried to steal the ballplayer’s cap. Jeff Burroughs kicked at the man but slipped and fell down. The rest of the Rangers, far away in their dugout, thought the men had knocked their teammate down. Billy Martin led his Rangers players onto the field. “Let’s go get ‘em, boys.” They sprinted to the rescue. They were brandishing every bat they had on the rack. When hundreds of fans poured out of the stands after them, with slats they had torn off from their seats, the riot was on. The law and order detail at Municipal Stadium on 10 Cent Beer Night was fifty older part-time men and two off-duty Cleveland policemen. They were swept aside by the flow of drunks. Some of the troublemakers were waving chains. Some had knives. Twenty police cars responded to the call for help. When they got to the ballpark they called for the Riot Squad. When the Riot Squad got there they called for more men. “We would have needed 25,000 cops to handle that crowd,” said Frank Ferrone, the Chief of Stadium Security. Tribe manager Ken Aspromonte ordered his players onto the field to help the Rangers. They armed themselves with bats and formed a phalanx. “They saved our lives,” Billy Martin said. “That’s the closest you’re ever going to see someone get killed in this game of baseball.” He didn’t know it got closer in 1920, when Yankee’s pitcher Carl May hit Indian’s batter Ray Chapman in the head with an errant fastball and killed him. A Cleveland player was hurt the worst during the riot when a flying metal chair hit him in the head. He had to be helped off the field. Nestor Chylack’s hand was badly cut and he was hit by a flying chair as well, before finally declaring the game a forfeit. The mob was incensed. More chairs went airborne. “They were f*****g animals,” the injured home plate umpire said. ”I’ve never seen anything like it, except in a zoo.” The organist played “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” over and over again. Some fans ripped the padding off the third base line fence. They stole all the bases. “This is an absolute tragedy,” declared Joe Tait, one of the broadcasters. “I’ve been in this business for 20 years and I have never seen anything as disgusting as this. I just don’t know what to say.” When beat reporter Dan Coughlin tried to interview a rioter, he was punched in the face. When he tried to interview a second rioter he was punched in the face again. After that he put his notebook away and went looking for a drink, something stronger than beer. There was no charm in trying a third time. Mike Hargrove had a chunky teenager on the ground and was walloping him. “That kid came up and hit him from behind is what happened,” said Herb Score, the other broadcaster. When the ballplayers fought their way back to their clubhouses, they bolted the doors behind them and left Municipal Stadium under escort of armed guards. The Riot Squad flooded the field with tear gas. “It’s not just baseball,” Ken Aspromonte said. “It’s the society we live in. Nobody seems to care about anything. We complained about their people in Texas last week when they threw beer on us and taunted us to fight. But look at our people. They were worse. I don’t know what it was, and I don’t know who’s to blame.” When the fireworks were all over we walked to Superior Ave., went across the bridge over the Cuyahoga River, and crossed West 25th St. We passed the one-sock streaker. He looked like he was wearing somebody else’s clothes. He still had on one black sock. We walked to the Big Egg, where we got late-night grub, mainly hash browns and fried eggs. They hadn’t run out of that day’s gravy. Their sauce was boss. The Big Egg wasn’t the cleanest diner in town, but it stayed open all night and the food was dirt cheap. Their slogan, on the wall behind the long counter, was “Where the Egg is King, and the Queen is, too!” Bobby Dunn, a Cleveland policeman and the owner, made sure the coffee was strong, if only for his own sake. “I don’t look at it as a black eye at all,” Carl Fazio said afterwards about what took place that night. “It was just one of those crazy things that happened because of a crazy set of circumstances that all came together that night.” The next day the Tribe slugged five home runs, pummeling the Rangers in front of 8,000 spectators. The stolen bases were never recovered. New ones were put in place. My friends and I stayed home. I read about the second game of the series a day later in the Cleveland Plain Dealer. The fans were well-behaved, cheering their heads off but not throwing anything onto the field. They sipped their beer before tossing their plastic cups under the seats. It was a breezy refreshing evening with bright stars high in the sky. Everybody kept their cool and kept their clothes on, too. Ed Staskus posts on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybook.com. © 2023 Ed Staskus |

StatsAuthorEd StaskusLakewood, OHAboutEd Staskus is a free-lance writer from Sudbury, Ontario. He lives in Lakewood, Ohio. He posts on 147 Stanley Street http://www.147stanleystreet.com and Made in Cleveland http://www.clevelandohiodaybo.. more..Writing

|

Flag Writing

Flag Writing