Mopsos XIIIA Story by Daniel EavesA short thriller revolving around the concept of instantaneous space travel.

I’d always imagined Pluto as blue, but as the

Mopsos XIII came in for contact it appeared to us dark, like a roughshod ball

of lead.

CLANG!

Even the

teeth-setting landing felt to us metallic. That was most likely all Mopsos, a

sturdy hunk of metal impacting a cold, hard planetoid three-and-a-half billion

miles distant from the sun.

The hatch floated open and my two crewmates and I

stepped out, three bulb-headed aliens bouncing into the frozen night wastes of

Pluto " the first of our kind. From here the sun appeared as little more than a

bright star, so our operations were lit by the bleak lamps housed in the

exterior of the Mopsos. Captain Pederson pressed a button in his suit and a

large central section of the ship unfolded on hydraulics, neatly laying out all

that was necessary for the construction. Then Corporal Baumann took magnetic

bearings and, using her divot tool, marked out the exact spot where we were to

build.

We set to, loading at first the giant base-struts

onto robot trolleys, two to a strut. They ferried them to the construction site

and lay them carefully on the solid surface. As we bounced back and forth with

rucksacks of bolts and seals my mind went back to the problem I’d had 8 months

to ponder: what was I doing here? As a theoretician it had personally been too

good an opportunity to pass up, but a niggle about the motives of the ESA, ignored during

training, had had plenty of opportunity to seed and grow on the outbound

journey. I had my guesses, and now that we were approaching zero hour paranoia

was setting in, making it hard to focus on the task at hand.

My name - Andrew Sally - was famous in the world of

physics, both in respect and ridicule. For a while I had been at the forefront

of Half-unified Theory - the most complete theory we have to date - and was considered then the most

authoritative theoretical scientist in the world. Then I published what has

become cruelly known as Sally’s Bogus Theorem, a misnomer that suggests that I

was attempting to hoodwink everyone. I wasn’t.

My Bogus Theorem (I call it that too, to confound

my critics), attached to general relativity, basically states that time is

related to distance in a manner that is visually observable. That is, the

further away from you an object is, the further in your past it is (as time is

relative to each person). This is observable to any human looking into the sky

at night. He sees stars millions if not billions of years in the past.

According to the calculations of Bogus Theorem, if we could find a way to

travel instantaneously from point A " that is with zero time passing from our

perspective - to, for example, point B at a distant galaxy, then when we

reached the galaxy it would be in exactly the same state as we observed it at

point A - ergo, we would have travelled billions of years into the past.

The scientific community ridiculed me, poked holes

in the calculations. I went away, recalculated and retracted the theorem. It

went completely against a number of laws related to the speed of light, and in

the end I was convinced it was impossible. After that, only my progressions in

space travel theory kept me afloat in the community. Why had that community

sent me here?

The sharply contrasted images of my comrades

bounded towards me.

‘Are you well, Sally?’ huffed Pederson through the

com, in his bold, Norwegian accent.

‘I’m fine.’

‘Keep focussed. Not long now.’ He tapped my

shoulder - a gesture I could not feel through my suit - and leapt once more

towards the pile at the ship. I pushed forward with a pneumatic wrench perched

in my glove to perform my assembly function at the construction site.

It was all done in six hours. Above us loomed the

fruit of our labour: a gigantic tunnel comprised of five septagonal frame sections, capped at one

end with an engine-like structure, looking to all intents and purposes like a

demonic machine from a steel refinery in space.

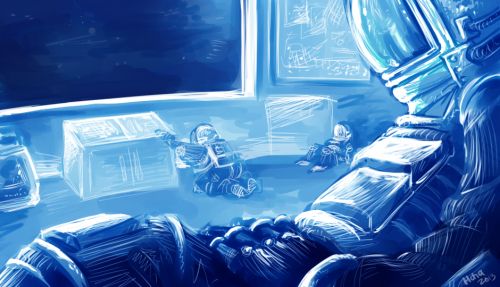

We climbed back into the Mopsos XIII, negotiated

our way to the cockpit, and strapped in. Soon it would be time. Pederson guided

our craft gently over the surface and into place, aft-first into the tunnel.

Now it was my turn. I unlocked the heavy, metal cover from the control panel

and primed the controls. The display showed robotic ballasts coming out of the

tunnel housing and attaching to the ship at my command. Baumann set the mark.

The timer started counting from 7 minutes down to the time we would be at the

correct spatial coordinates. Silence. For all the weightlessness of Pluto, the

weight of a history-defining mission on our shoulders.

5 minutes.

Baumann was

flexing her hand nervously, still gloved in its suit. As we didn’t know what

was about to happen we had elected to keep them on in case of irregularities,

unforeseen dangers.

‘Inner peace, guys,’ counselled Pederson,

uncertainly.

3 minutes.

I could

sense the blood pumping and swilling around my head. In all this time in space

I had never felt claustrophobic until now. My thoughts wandered over that

period through the void, travelling at an average of 625,000 mph; all the

banal, civil relations with my crewmates. Things would be moving much faster

soon, if you could call it moving.

Suddenly it was there before me: 5… 4… 3… I unlocked the safety with a

turn of a knob and pressed the button for Green Light. The ship did the rest.

Nothing. Then, an increase in light, a sense of

searing heat around the ears, space dropped away into a kaleidoscope-coloured

surreality, a sickening lurch as though being thrown down a canyon from the

window of a high speed train, and the next second really nothing.

I awoke to find myself sprawled in the hollow

underneath the main control panel, blowing bubbles in a pool of my own vomit,

which had collected at the bottom of my visor.

I looked weakly across the cockpit. Baumann was sat

foetally up against the wall, helmet off, her hair drenched with the contents

of her stomach, her broad, Germanic face deathly ashen, looking down and seeing

nothing.

Pederson had somehow ended up at the far end of the

room. He was lying prone on his back. He wasn’t moving.

Worried that he may have choked on puke, I crawled

towards him and released his visor. He had vomited, but beads of sweat and deep

panting assured me that he lived.

The next day we were able to check our position.

‘I don’t understand,’ said Baumann, ‘32533 X-T1

should have compacted into a regular spiral galaxy by now, did we come the

wrong way?’

‘That’s 32533 X-T1,’ I replied, ‘look.’

I showed her photographs taken by the Solar Scope

probe from our system, pointing out manifold correlations. From that distance

the image of the galaxy was billions of years old, and yet it hadn’t aged a

day. A radiographic survey confirmed it.

‘Then you’re not so bogus after all, Dr. Sally,’

Pederson joked mirthlessly. Our instantaneous travel, which was supposed to have

taken us billions of light years in distance - to the source of what appeared

to be a time-and-space distorted, yet intelligent signal - had also taken us billions of years into the

past, as Bogus Theorem predicted. There would be no return. We had the

equipment to build a second tunnel, but the Milky Way would have been in a

primordial state when we got there.

Baumann brightened suddenly, ‘but that means that

we’ve not only arrived at the source of the signal, but at the time of it too!

We can’t return, but maybe we can make contact!’

We had always been aware we probably weren’t coming

back; this at least was an exciting step forward. ‘Send a message,’ I said.

She rushed to the communication panel. ‘This is

Stefanie Baumann, speaking for the human race, we come in peace. Can anyone

hear me, over?’

She repeated it a few times. Pederson stood

observing, arms folded.

‘How long will the message we just sent take to get

back to the Earth?’ He asked at last.

I did the mathematics quickly in my head, and then

it dawned on me. I slumped down, sickened by the irony of it.

‘It’ll arrive exactly at the time Ears on the

Universe picked up the alien signal originating here,’ I told them. And we floated on without aim. © 2013 Daniel Eaves |

Stats

265 Views

Added on September 3, 2013 Last Updated on September 3, 2013 Tags: time travel, sci fi, Pluto, inter-galactic, space, philosophy, science Author

|

Flag Writing

Flag Writing